Benito Bowl 2026: A 500-Year-Old Wake-Up Call

The sound of ancestral memory on the world's biggest stage

This article is a guest essay written by Sam Floyd

Another epic Super Bowl halftime performance is in the books, and the U.S. is left doing what it always does afterward: telling on itself.

From the moment Bad Bunny was announced as the headliner, there was both excitement and a predictable, loud backlash. On one hand, we had the reality of the Americas: a vibrant mix of cultures, including a Latin one that dates back centuries, proud to finally see itself represented by a conscious Puerto Rican artist on the world’s biggest stage. On the other hand, a vocal faction of the U.S. status quo continues to read inclusion as displacement.

That second faction didn’t just complain; they tried to counter-program. They organized an “All-American” alternative halftime show featuring Kid Rock. But the numbers don’t lie: while Benito drew a record-setting 135.4 million viewers, the alternative show limped along, peaking at roughly 5.2 million concurrent live viewers on YouTube. Even the Puppy Bowl had more juice online. They can be mad all they want, but they simply don’t have the sazón.

The Language of Resistance

With almost no English, and the mic fully on, Bad Bunny delivered a performance that pulled massive numbers and dominated the global conversation. Despite the language barrier, the messaging—much like Kendrick Lamar’s last year—came through with total clarity.

I’ve seen plenty of breakdowns of the symbolism, and I’ll be the first to admit: someone native to Puerto Rican culture can interpret the nuances better than I can. But what I felt, as a Black American, was a shared history of, and triumph over, ethnocide: the systemic destruction of a people’s ancestral culture to facilitate perpetual exploitation.

In this way, Latinx culture is inseparable from Black culture.

The discomfort some felt watching a Spanish-language performance wasn’t just about music; it was a modern echo of centuries of erasure. We often get stuck on surface differences—the fact that Black folks speak English and Latinx folks speak Spanish. But the harsh reality is that for many of us, our Indigenous tongues are unknown. Both English and Spanish functioned as tools of empire, replacing native languages through conquest. Within that paradigm, the African diaspora was forced to master these colonial tongues just to survive.

By centering Spanish on the Super Bowl stage, Benito turned a tool of the empire into a shield of resistance.

Discovery as a PR Campaign

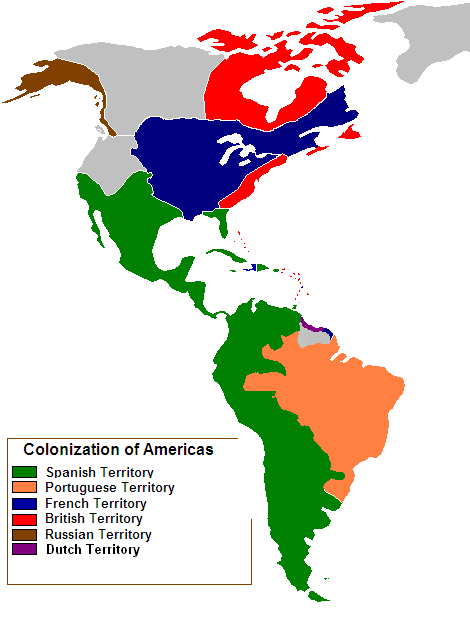

We are in a moment where history is being actively whitewashed. We’re taught that Christopher Columbus “discovered” America, yet he never set foot on the U.S. mainland—his first landfall was in the Caribbean. Even the naming of “America” itself was essentially a 16th-century PR campaign. Amerigo Vespucci’s published letters and Europe’s mapmakers narrated, packaged, and sold this hemisphere to Europe through maps and prestige.

The story of “discovery” was never about geography. It was about power: who gets to name, who gets to define, and who gets to claim.

To say the quiet part out loud… There is a distinct connection between Black and Latinx cultures, because we were integral human capital in building this so-called “Land of the Free,” whether the country wants to admit it or not. On this side of the planet, the one-drop rule is the ugliest shorthand for a broader truth: white supremacy taught the Americas to treat African and Indigenous ancestry as a stain, regardless of language, passport, or proximity to whiteness.

That’s why Spanish vs. English is a distraction. The deeper issue is who gets to belong, and on what terms.

So when Bad Bunny opened the show in the sugarcane fields of Puerto Rico, I felt that. When he showed bodegas, nail salons, and barbershops in New York, I felt that. When the dancers moved their hips to rhythms with African lineage, I felt that. Even when I didn’t understand every word, when I heard the sounds of Afro-Caribbean music and percussion, I felt that.

To be honest, I knew many of those sounds, but I didn’t know the names until Googling them to write this. That’s part of what the performance did. It taught. It tapped into ancestral memory.

The Ongoing Struggle

This is the power of what Benito pulled off. He connected nearly every country on this side of the planet through our shared, twisted history. It is a history where survival requires preserving culture and finding joy in the small things—family, community, and rhythm.

We have always been in an international struggle against colonialism, whether in Puerto Rico, Hawaii, New York, Los Angeles, Texas, DR, Jamaica, Cuba - pick a place. Fascism requires the creation of an “Other,” and America perfected a version of racial hierarchy so influential that the architects of Europe’s darkest regimes studied the Jim Crow South as reference material.

Today, the logic used by ICE across the country echoes the enforcement regimes empowered by the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1793 and 1850. Both systems rely on broad discretionary power to monitor, detain, and displace people. Our physical and cultural struggles on this land are, and have always been, shared.

So I couldn’t help but see myself all up and through Bad Bunny’s performance, even if I didn’t understand many of the words.

Still Here

Even though Benito did manage to utter three English words: “God Bless America” —

Even though we can all understand the English words printed on the football at the end: “Together, We Are America” —

Even though the English words on the billboard as all the North, Central, and South American flags were hoisted down the field read: “The only thing stronger than hate is love.” —

It is unsurprising that people were upset by a show they perceived as “un-American” because it wasn’t centered on whiteness. That reflex is predictable. But as the countries across the Americas’ flags were hoisted down the field, the message was undeniable.

The most important thing Latin Americans and Black Americans have in common despite the many forces in play is simple:

SEGUIMOS AQUÍ — WE’RE STILL HERE.

When you understand how much of “history” is a curated story built to justify power, the bewilderment over a halftime show in Spanish looks less like a cultural clash and more like a refusal to wake up from a 500-year-old dream.

So big salute to Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio, who, in bringing the world to Puerto Rico for the Super Bowl Halftime Show, reminded us all what it means to be a real American.

This, too, is Black history. And I’m damn proud of it.