How the Fugitive Slave Act Helps Explain ICE's Terrorism Today

By Knowing This History We Can Learn How to Respond to ICE's Terrorism by Reconstructing a Better America

I started working on this article last Monday, and as the crisis in Minneapolis grew during the week, so did this article. This is the one of the longest pieces that I have written for The Reconstructionist (3,500+ words). Words are not enough to describe this crisis, but words are still necessary for describing this crisis.

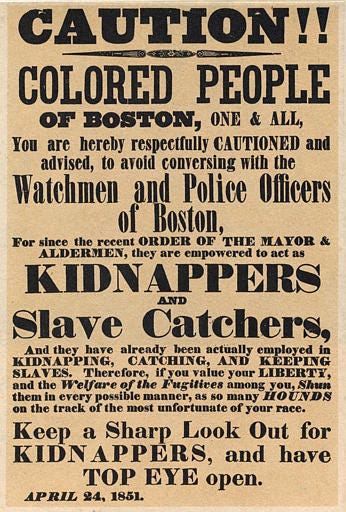

When I look at ICE’s escalation in Minneapolis, I keep on thinking about the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that made it legal for mercenaries to invade Northern states so that they could hunt down and capture escaped slaves and send them back to Southern slaveowners.

A month ago, this claim might have sounded outlandish, but it no longer does following the murders of Alex Pretti on January 24 and Renee Good on January 7, and the increased ICE presence that has occurred this month.

ICE’s brazen disregard for the law mirrors the actions of the Southern mercenaries/bounty hunters from the 1850s. Legally, they were only allowed to capture escaped slaves, but the nature of their job made it incredibly difficult to prosecute these bounty hunters if they strayed beyond the law and instead racially profiled Black Americans in the North, and kidnapped Black Americans who were free residents in the North and not escaped slaves from the South.

Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s recent decision in Noem v. Vasquez Perdomo that justified the racial profiling of Latinos by ICE adheres to the same logic from 1850 that justified Southern mercenaries invading Northern states. In both cases, there appears to be an unfounded belief that these Americans—bounty hunters in the 1850s and ICE agents today—will have a pristine moral clarity that will ensure that they will never stray outside the confines of the law even though it will be incredibly difficult to punish them if they do so. Then as now—and to Kavanaugh’s apparent surprise—this theory has been proven wrong, and “Kavanaugh stops” have become a normal part of ICE’s agenda.

As Trump’s authoritarian agenda grows increasingly violent and deranged, it is easy to compare it to authoritarian regimes from other countries, but this comparison misdiagnoses the problem. The violence we are seeing today is not the manifestation of a foreign form of authoritarianism arriving in America. Today’s violence is the manifestation of a distinctly American iteration of authoritarianism and terror, and the more reluctant we are to admit this uncomfortable truth, the less likely we are to defeat it. Yes, we can compare ICE to the Gestapo and the Trump administration to Nazis, but the most accurate comparison is to the slave catchers, mercenaries, bounty hunters, and Southern politicians from the 1800s.

The Fugitive Slave Act de facto allowed for the hunting and kidnapping of all Black Americans in Northern states. The only refuge for Black Americans resided in either their ability to show these Southern bounty hunters their papers to prove their freedom or the protection of white abolitionist Northerners. Normally, Black Americans required both because Southern bounty hunters had no qualms about kidnapping a free Black American and destroying their documentation if they supposedly fit the profile of an escaped slave. So long as they got paid, they did not care if they captured the right person. To prevent these kidnappings, force needed to be countered with equal force.

This same dynamic is currently at play in Minneapolis, yet to adequately understand the parallels between ICE and the Fugitive Slave Act, we must acknowledge that both of them are a manifestation of the way of life and ideals of the pre-Reconstruction South and their spread beyond the South into the rest of the nation. Additionally, it is imperative that we understand the significant, yet mostly unknown, role Minnesota played in America’s pre-Civil War battle over slavery.

Minnesota and Dred Scott

Minnesota became a state in 1858, having been a U.S. territory since 1849, but the American military has had a presence in the area since 1819 with the creation of Fort Snelling, which was located along the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. As Fort Snelling’s population grew in the 1800s, a city began to form that would officially be founded as Minneapolis in 1854.

From the beginning of the United States, the American South sought to expand slavery beyond the South, and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 stipulated that slavery was illegal in territories north of the 36°30’ parallel. Despite being illegal at Fort Snelling, slavery was still prevalent in the area, and its prevalence was due to the U.S. government. American servicemen stationed at Fort Snelling were given a stipend to hire an assistant, but it was common for them to bring an enslaved person instead and pocket the money.

Fort Snelling is an example of normalized lawlessness within the American military dating back to 1819.

Even though slavery was outlawed in Minnesota, which was part of Wisconsin Territory, it became a fertile ground for enslavement because the lack of state or federal courts meant that the enslaved population had no legal recourse against their enslavement. In order for an unlawfully enslaved Black American to obtain their freedom, they would need to escape to a state and challenge the legality of their enslavement in court. In the 1830s, two enslaved Black women, known only as Rachel and Courtney, in separate cases, challenged the legality of their enslavement at Fort Snelling in Missouri courts.

In Rachel’s case, the St. Louis Circuit Court denied her claim for freedom arguing that her enslaver, T.B.W. Stockton, who was an officer in the United States Army, could not control where he was stationed, therefore, it was not his choice to take Rachel to a free state and it would be unfair to deny him of his property.

Rachel appealed the decision to the Missouri Supreme Court and in Rachel v. Walker (Stockton sold Rachel and her son James Henry to William Walker), the court granted Rachel her freedom due to her living in a free state, which rendered her enslavement there illegal. Soon thereafter, Charlotte filed a similar suit and her freedom was also granted.

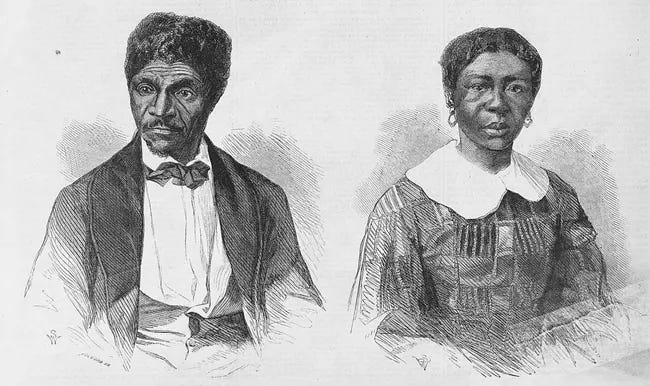

A decade later, in 1846, two Black Americans also enslaved at Fort Snelling, Dred and Harriet Scott, would file a similar lawsuit in St. Louis. It is believed that one of their reasons for pursuing their freedom was that their daughters were approaching the age where they could be sold for a good sum of money, and that acquiring their family’s freedom would prevent them from being broken apart.

The Scotts anticipated that their case would be simple and straightforward due to the success of Rachel’s, but a strange legal technicality and the changing political winds of the time turned their lawsuit into one of the most controversial Supreme Court cases in American history.

Due to a procedural error, the Scott’s case dragged into the 1850s, and following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, the courts began to challenge the legitimacy of the precedent that living in a free state could grant an enslaved person freedom. Since it was now legal to kidnap a formerly enslaved person residing in the North and return them to their slave owner in the South, the precedent set in Rachel v. Walker was now being challenged.

In 1852, the Missouri Supreme Court decided against granting the Scotts their freedom. The Scotts and their attorney then took their case to federal court and, in 1857, in Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court not only denied the Scott’s their freedom, but also ruled that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional.

The Dred Scott case is regarded as one of the worst decisions in the history of the Supreme Court, but as we address our current constitutional crisis and the deadly threat posed by ICE, it is imperative that we understand that the foundation of this decision consisted of both denying the humanity and legal status of people residing in the United States, and completely disregarding the legal precedent and rights afforded to these people less than a decade before.

If the Missouri Supreme Court had heard the Scotts’ case before 1850, they probably would have been granted their freedom, and most Americans would not know the name Dred Scott. But by 1850, politics had corrupted the courts, and precedent had become essentially meaningless if it did not support the expansion of slavery or the protection of white property.

Arresting Latinos and other immigrants at their immigration check-ins as they attempt to follow the rules and pursue American freedom is a modern-day equivalent to Dred Scott. In the 1800s and today, Minneapolis seems to be at the epicenter of both.

A Pro-Slavery Society – Understanding the Present by Going Back to 1850

Prior to the Reconstruction Amendments that abolished slavery, created birthright citizenship, extended voting rights to Black men, and made the Bill of Rights federally enforceable, the role of the law in American society barely resembled what it is today.

Civil rights were incorporated into American law during Reconstruction and, before then, citizenship was considered an entitlement for whites alone. Additionally, the main purpose of the U.S. Constitution was to manage the relationship between the states and federal government, and to protect the property rights of white Americans. It evinced no interest in protecting the rights and freedoms of vulnerable minorities against misconduct by all levels of government.

Instead, it existed to balance the interests between the slave owning and non-slave owning states, which resulted in the de facto and de jure legitimization of slavery. Despite not mentioning slavery at all, the U.S. Constitution was a pro-slavery document, which becomes clear upon examining how it distributed power in the government.

For example, the three-fifths compromise counted enslaved people in the South as three-fifths of a person for purposes of congressional apportionment, thereby giving Southern states increased representation in the House because of slavery. Additionally, congressional apportionment also determined each state’s Electoral College representation. The enslaved could not vote, but their enslavement sent more enslavers to Congress and helped many Southern politicians become president. It is not a coincidence that nine of America’s first fifteen presidents came from the South, and all of them, except John Adams and John Quincy Adams, would be described as pro-slavery presidents.

In Federalist Papers 54 and 55, James Madison—who would go on to become the fourth president—justified the three-fifths compromise by explaining how enslaved people were both men and property, yet a lesser form of man; therefore, they should be legally stripped of two-fifths of their personhood with regards to representation. Additionally, he stipulated that American laws have taken away their rights and reduced enslaved people to property, and that if these rights were restored there would be no justification for counting them as three-fifths a person.

Due to the South’s interest in continuing the enslavement of African people and viewing them as property, the founders of the United States decided that our “democracy” needed to have a weak federal government that mostly refrained from interfering in states’ rights, including the right to enslave people, yet the federal government also needed to protect white property, which included their enslaved people.

According to the Constitution, Dred Scott and his family could not become free people because their freedom would equate to denying white Americans their property.

This attempt to balance the interests of the slave owning and non-slave owning states shifted the balance of power in favor of the anti-democracy, pro-slavery voices in the South. As a result, the United States created a pro-slavery Constitution without explicitly mentioning slavery at all. This really is an ingenious bit of legal and linguistic sleight of hand, in that the document appears to profess one set of ideals while manifesting opposing outcomes. The Constitution’s pro-slavery leanings were so pronounced that even anti-slavery presidents felt obliged to honor them.

“God knows that I detest slavery, but it is an existing evil, for which we are not responsible, and we must endure it, and give it such protection as is guaranteed by the Constitution,” said Millard Fillmore, the thirteenth president, regarding the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 that he signed into law.

Fillmore might have detested slavery, but in signing the Fugitive Slave Act, he must be regarded as a pro-slavery president. Fillmore’s position is not dissimilar to that of Democratic politicians who claim to dislike ICE, yet continue to support legislation that funds it.

The Fugitive Slave Act was the logical extension of the federal government’s attempt to balance the interests of the slave owning and non-slave owning states, while also trying to avoid interfering in states’ rights and attempting to protect the property rights of white Americans. This is American “logic” prior to Reconstruction.

As Minnesotans appear to have very few legal recourses to prevent the actions of ICE, and the Trump Administration continues to act as though civil rights do not exist, we are witnessing an American legal regression, or degeneration, into a pre-Reconstruction iteration of American law and society.

The chaos caused by ICE in Minneapolis, and also in Chicago, Portland, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and many other cities across the country, merely represents an attempted return to a pre-Reconstruction status quo. Compared to the 1850s, today’s violence is still less severe than in the past and, due to Reconstruction, American citizens still have more rights and legal protections than the Americans from the 1850s, but as conservative jurists and the Trump administration continue to apply an originalist interpretation of the law, we should anticipate a continued regression and degeneration of American society and law.

When the South Becomes Federal

In comparing ICE to the Fugitive Slave Act, the key discrepancy between the two is that the former is a federal agency and the latter was a law, yet this distinction misses the forest for the trees. Also, the emphasis on federalized terror inclines people to compare ICE to the state sponsored terror that has occurred in other countries, which misses both the forest and the trees.

The bounty hunters in the Fugitive Slave Act did not work for the federal government, but they would have if they could have. A decade after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act, these bounty hunters became soldiers in the South’s new federal government, the Confederacy.

Following the South’s defeat in the Civil War, former Confederate soldiers began forming militias such as the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize the newly-free Black Americans and their white allies, and to suppress Republican voter turnout. During Reconstruction, the KKK became the de facto military arm of the Democratic Party in the South. In order to allow for democracy to emerge in the South, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1870, also known as the Enforcement Act or Force Act, that empowered the American military to use force to protect the civil rights of Americans in the South. That same year the Department of Justice was created to prosecute individuals who infringed upon another’s civil rights. As a result of the Force Act and the DOJ, the Ku Klux Klan was defeated and disbanded in the South and did not re-form until 1915.

During the Jim Crow era following Reconstruction, the descendants of the bounty hunters, Confederate soldiers, and Klansmen professed a cultural narrative that celebrated their ancestors. They also brought back the KKK and normalized their terrorizing of Black Americans. These people also formed the backbone of Southern law enforcement and government. Racial division, violence, and unaccountability had returned as the South’s cultural norm, and they did not fear that the federal government would intervene to protect the civil rights of its Black citizens. Southern states espoused a belief in states’ rights and expected the federal government to not intervene.

The South’s dystopian norm remained unchallenged until Americans outside the South were able to see the brutality, the horrors of which exceeded many Americans’ wildest imaginations. The murder of Emmett Till in 1955 helped launch the Civil Rights Movement, and the images from Dr. Martin Luther King’s march in Selma, Alabama, in 1965, made Americans aware that law enforcement, and not just racist vigilantes, were attacking and murdering Black Americans.

In the 1960s, the South’s ideological reach was mainly regional, so that was the ceiling of their terror. In the 1850s, bounty hunters extended their ideology into the North, and during Reconstruction, their ideology created the KKK. Today, it has gone national and become the ideology of the Trump administration and his federal government. The Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, white nationalists who marched in Charlottesville in 2017, and Trump supporters who attacked the Capitol on January 6th have now become part of ICE. This is what it looks like when the Old South becomes federal.

The events in Minneapolis, both the peaceful protests and the violence by law enforcement, mirror the events and images from the 1960s. On Saturday, January 24, Alex Pretti was murdered in broad daylight by ICE agents, and the video of his murder is all across the internet. Americans are seeing a level of horror and terror that they thought was unimaginable, like Selma, the murder of Emmett Till, and the Fugitive Slave Act. We do not have photos and images from Fugitive Slave Act enforcement, but if we did, they would look a lot like Minneapolis.

Since the inception of America’s democracy, federalism and states’ rights have primarily existed as a means for the South to continue their oppressive, anti-democratic agenda. So when Americans who adhere to the ideals — essentially, white supremacy – control the federal government, they will use their power to spread violence, racial division, and authoritarianism, and destroy our democracy.

The Democracy to Come: When Civility Defeats Incivility

In times of crisis, it makes sense to think about the actions we must take to combat the crisis. We need to respond to the attacks, but this response, regardless of good intentions, is often short-sighted and reactionary. It lacks the proactive, philosophical underpinnings required to sustain a movement.

The large-scale marches, protests, strikes, boycotts, and community organizing that we are witnessing in Minneapolis are inspiring the nation, but in order for these efforts to succeed there needs to be a philosophy that can sustain this energy—not just in Minneapolis, but across the nation—for months and years to come. Reconstructionism is that philosophy because it re-connects Americans to their history so that they can better understand their present, and it also gives a philosophical framework that can shape our actions.

Knowing about how Americans in the North responded to the Fugitive Slave Act can help guide our response to ICE today, and this will help us create the democracy to come (la démocratie à venir).

When President Fillmore signed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, his decision was viewed as a moderate one that could maintain the balance between the North and the South, preserve the Union, and defend the Constitution. He was not a pro-slavery radical, but the presence of bounty hunters did radicalize many people in the North into becoming staunch abolitionists.

Prior to the Fugitive Slave Act, many Northerners had little conception of the brutality of slavery in the South. They might have had moral or religious objections to slavery, but they had no idea what it looked like. These bounty hunters let them see a sliver of the brutality of the South, and they became horrified.

In 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe, who was from Connecticut and had never been to the South, published Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Through interviewing escaped slaves in the North, she depicted the horrors of slavery in the South to her Northern audience, and her novel became the most popular book in America.

In 1854, abolitionist Northerners created the Republican Party and its main political platform was the opposition of expanding slavery into the new U.S. territories. This advocacy drove the dissolution of the Whig Party, which could not decide whether it was for or against slavery. The era of moderates had ended, and a new political movement was born. Six years after the party’s inception, Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won the presidency.

None of these events were inevitable or part of the natural trajectory of America. The steady expansion of slavery had been America’s norm. These events are l’à venir or the unplanned future to come that arrives when we encounter the Other and express our humanity and not our barbarity. Rachel was an Other, the Scott family was an Other, and sharing our humanity with them created a new American future.

Colonization welcomes the Other with barbarism, genocide, ethnocide, enslavement, and terror; and as a result, the future becomes predictable. The future will always consist of the Other fighting for their freedom, and the oppressor denying the Other’s freedom so that they can sustain their oppressive way of life. This was the predictable future that America was built upon, but our society became gloriously unpredictable once we welcomed Black Americans, the Other, with kindness and friendship. Few would have predicted a future where the Republican Party controls the White House six years after its inception and then wins the Civil War, yet it happened.

Fifteen years after the Fugitive Slave Act, we had the Thirteenth Amendment that abolished slavery in America. Reconstruction turned the Constitution into a pro-democracy document and consciously worked to remove all vestiges of slavery from the Constitution. In 1850, this transformation seemed unlikely at best, yet it happened.

The Fourteenth Amendment and birthright citizenship radically changed American immigration and eventually America became known as a democratic society that welcomes immigrants from around the world regardless of race, religion, or ethnicity. America became a more authentic and legitimate democracy by embracing the Other, and the 1850s were a pivotal moment in making this profound change. Today also feels like one of those pivotal moments, so we must embrace the unpredictable future to come that is driven by new people and new ideas. We know the predictable future shaped by moderates and the status quo, and we do not want to continue that regression.

This is the democracy to come. This is Reconstructionism. We must resist American authoritarianism through protests, boycotts, marches, strikes, art, literature, and votes; but we also must know that we are capable of creating new forms of resistance and reconstruction.

This is how positive change has always occurred in America, and knowing this history empowers us to create a better future.

Yes! Knowing this history empowers us to create a better future. Thanks for sharing your insights and knowledge with us, Barrett. We must remain steadfast against the tyranny and insanity of the Trump administration.