How to Understand and Defeat American Fascism

Our Society Mistakenly Focuses on the Symptoms and Not the Causes of Fascism

As the violence of President Donald Trump’s agenda increases, spreads, and becomes impossible to ignore, most Americans have come to the realization that fascism exists in America, but they have yet to realize what causes fascism and that American fascism is not a replica of European fascism.

Since Americans do not know what causes fascism, we are left with diagnosing the symptoms. We believe that fascism exists in America once we agree that Trump’s actions resemble those of the fascist movements in Europe such as the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany and Benito Mussolini in Italy. Yet this approach means that Trump can only become a fascist in the eyes of the American public once he has the authority to implement a fascist agenda. This approach, obviously, makes it much harder to stop fascism in America.

In an article for The New Yorker published on November 8, 2024–soon after Trump won the presidency for a second time–titled “What Does It Mean That Donald Trump Is a Fascist” historian and former Yale University professor Timothy Snyder described how Trump’s actions mirror European fascism, how Americans were reluctant to believe that he could win the presidency again, and how since 2015, Trump’s actions were “treated as a source of spectacle.” Essentially, on November 6, 2024, Trump’s return to the presidency, and the power that comes with it, meant that his actions had meaning and were more than merely spectacle. In early 2025, Snyder left Yale and the United States, and emigrated to Canada to escape American fascism.

For many Americans, Trump’s re-election ended the spectacle, but I believe that Trump’s and ICE’s actions in Minneapolis have been the tipping point for most Americans that ended the “spectacle.” January 2026 is when most Americans accepted the reality of fascism’s arrival.

For over a decade, Americans have been reluctant to acknowledge the presence of fascism in our country–by not knowing the causes and denying the symptoms–and I should know, because I attempted to sound the alarm over a decade ago.

In August 2015, in a column for The Daily Beast titled “Ok, This Trump Thing Isn’t Funny Anymore,” I compared then candidate Trump to European fascists, but I also wondered why American society was reluctant to describe Trump as a fascist despite his campaign’s displaying many attributes of fascism. Trump’s rhetoric from the onset of his campaign reminded me of the language that has long been used to terrorize Black Americans. It reminded me of the stories my parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents have told me about the 1960s; and the family history that they’ve taught me dating back to the early 1800s. I know my history and this is why I knew Trump’s rhetoric was fascist.

In my book, The Crime Without a Name: Ethnocide and the Erasure of Culture in America, I describe how one of my editors at The Daily Beast proclaimed “You can’t call Donald Trump a fascist!” and how they let me write the story only after two Trump supporters, who were white men, beat up a homeless Latino man and said, “Donald Trump was right, all these illegals need to be deported.”

Yet even then, they would not allow my story to explicitly state that Trump was a fascist, only how his campaign resembles the European fascist movements of the early twentieth century.

At the time, I had a lot of internal pushback regarding this story because my editors felt it was “unfair” to describe Trump as a fascist. They felt the accusation was hyperbolic and unnecessarily controversial because they could not imagine Trump winning the presidency. Essentially, even if he was a fascist, it was irrelevant because he supposedly would never obtain the power to implement a fascist agenda.

To describe Trump as a fascist, my editors needed to see the symptoms, such as his thugs beating up a Latino man; but as a Black man in America, I already knew what caused fascism in America. While I could feel the trauma of fascism, ten years ago I did not yet know how to express it as succinctly as I can today, having spent more than a decade thinking about how to say it.

Quickly Understanding the Symptoms of Fascism

When people describe something as ‘fascist,’ they are normally describing the symptoms and attributes of fascism. We know what fascism looks like and feels like, but we are less clear about what causes fascism. Something happens and then we are tasked with examining the terror and determining whether these actions could be described as fascist.

Umberto Eco’s 1995 essay “Ur-Fascism” for The New York Review of Books is regarded as the best descriptor of the symptoms of fascism. In it, he points out some of the distinctions between Italian, German, and Spanish fascism, and wonders why “fascism” and not “nazism” has become the moniker for governments and leaders who show such symptoms. He also describes fourteen features of Ur-Fascism, or Eternal Fascism, that all fascist governments possess. The nature of fascism will look different from place to place, but most of these features will reside in all of them.

Also, according to Eco, a government and/or leader do not have to have all of these features, but they need to have what philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein would call a “family resemblance.” (For example, no two games are exactly alike, but you know that both of them are games because they have a “family resemblance” as games.)

American fascism does not need to look exactly like Italian, German, or Spanish fascism. It just needs to have a family resemblance. Today, the resemblance is unmistakable and American fascism certainly has all fourteen of Eco’s features of Ur-Fascism.

For example, the first feature of Ur-Fascism is the cult of tradition and this cult will claim to possess the foundational truths of the society. The cult’s purpose is to preserve these “truths” and “traditions,” but these claimed truths are not true and the traditions are just propaganda. Trump’s MAGA movement, American conservativism, and originalist legal theory all align with this feature. Also, the Trump administration’s policy of removing references of slavery and depicting white history in the most favorable light is an act to preserve these “truths.”

Features four and five state how Ur-Fascism hates disagreement and diversity. “Ur-Fascism is racist by definition” and fascists always attack the intruders such as immigrants. Trump’s immigration policies and his recent post on Truth Social depicting Barack and Michelle Obama as monkeys are examples of features four and five of Ur-Fascism.

(Eco’s fourteen features of Ur-fascism appear at the end of this article.)

Yet, the process of diagnosing the symptoms gets us no closer to understanding the causes of fascism. To truly understand American fascism, one must understand what causes fascism and not just recognize the symptoms.

What Causes Fascism?

Fascism occurs when people who are part of a community are forcefully and arbitrarily expelled from the community and turned into the Other. The symptoms of fascism are the actions that an authoritarian must engage in to justify, implement, and sustain the fracturing of their society.

To best understand the causes of fascism, one can take a closer look at the societal changes that were transforming Europe in the late 1800s and early to mid 1900s.

Modern fascism began with the rise of Benito Mussolini to Prime Minister of Italy in 1922 and lasted until he was overthrown in 1943, but to understand the causes of fascism in Italy, it is imperative that we understand the importance of the Risorgimento that created a unified Italy in 1861. Prior to the Risorgimento, Italy as we know it today did not exist. It was not a unified nation or kingdom. The people on the peninsula spoke Italian, but they pledged allegiance to the various monarchies that populated the peninsula and were not a united people. When the Risorgimento ended in 1861, the Kingdom of Italy was created, lasting until 1946.

From the 1860s to the rise of Mussolini, Italy and Italians had undertaken the complicated process of uniting as one people and creating a stable government. But Mussolini brought this progress to a halt. In 1919, he created the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian Fasces of Combat), which would become the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party, or PNF). Mussolini’s combat squad became his political party and members of the PNF called themselves fascista or fascist, which derived from the Italian word fascio, meaning “a bundle of rods or sticks” and intended to symbolize strength through unity – a bundle being harder to break than a single rod. The fascio also came to represent the club or bat that Fascists would use to attack their opponents.

Mussolini rose to power because his Fascist Blackshirts marched on Rome in 1922, demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Luigi Facta, and intimidated King Victor Emmanuel III into naming Mussolini as the new prime minister. Mussolini’s March on Rome is akin to the attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, except the former succeeded in putting the authoritarian in charge of the government.

In his quest to form a totalitarian government with himself at the pinnacle, Mussolini had to silence and intimidate his opposition, which became the Other. This is a common tactic for all authoritarians, but the trauma of becoming an Other becomes far more visceral and destructive in a society that has invested so much time and effort into creating a unified, common people.

Indeed, the trauma of creating an Other from a common people is the common foundation of fascism and why Germany and Spain, in the early to mid-twentieth century, were also described as fascist states. In 1871, Otto von Bismarck had overseen the unification of Germany, creating the first nation-state for a German people. Yet by 1933, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party rose to power through a movement intent on dividing that people. They preached a unity similar to the Fascists, but their authoritarianism and white supremacist ideology meant that their opposition, and non-Aryan people, such as Jews, Africans, and Slavs, became the Other. Despite having a different religion, it is clear that Germany’s Jewish population identified as culturally German. They believed they were part of the collective, and the Nazis made them the Other, culminating in the Holocaust. Germany is still trying to recover from this mass trauma.

Similarly, Spain in the 1800s was going through a tumultuous process of trying to create a unified Spain, but its various regions struggled to come together. Dictator Francisco Franco would exploit these divisions and pit Castilian Spain against Catalan Spain, thus carving out an Other from a people trying to make a collective.

Fascism shows that being citizens of the same nation-state is not the same as being a common people who see and respect the humanity of their neighbors. Rather, fascism is an example of a society destroying itself from within.

The similarities of these three authoritarian regimes, and the fact that they collaborated with each other, make it somewhat logical to define them by their shared features and use that as a rubric for understanding other authoritarian regimes. But, again, to truly understand American fascism, for example, one must understand its distinct causes and not simply its common features.

American Fascism

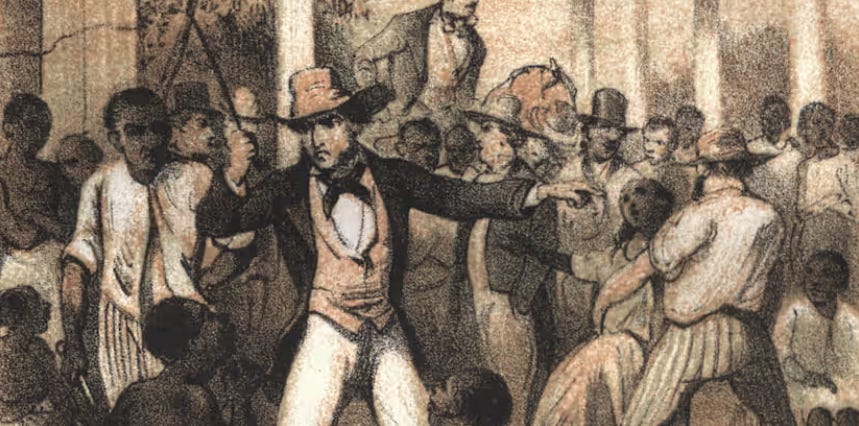

Despite naming itself the United States of America, American society has always been built around racial division. European colonizers never had a desire to unite with Indigenous peoples. In fact, one of the biggest conflicts between the American colonies and the British monarchy was the colonists’ refusal to respect treaties between the British and Indigenous peoples, because they wanted to invade Indigenous land.

Likewise, the transatlantic slave trade brought thousands of African peoples to the United States, and Europeans had no desire to unite with these African people, either. The racial identity that Europeans created for themselves stipulated that mixing with any non-white race would result in the erasure of one’s whiteness.

Whiteness existed as a zero-sum identity, which is important for understanding American fascism in that whiteness in America created an Other per se. Thus America has never had a truly common people comprised of all persons who live there; rather, white people are the “common” people and their values the “common” values.

As a result, when terror befalls Black Americans, American society, filtering it through the lens of whiteness, does not experience it in common but regards it a Black experience – something that happened to the Other. The trauma is not societal, but particular. But for Black Americans, who have always fought to be considered part of America’s common people, the terror and trauma are generational, profound, and enduring. That dichotomy of experience is, in essence, American fascism.

Tragically, American society will normally dismiss, minimize, or rationalize the righteous claims of Black Americans because the terror they have endured (and endure) has not impacted the “common” people. I have been describing Trump as a fascist since 2015, but in the United States, the “common” people will believe that fascism has arrived only when white people are terrorized and been made an Other.

In 2020, George Floyd was killed by American law enforcement in Minneapolis, but his murder was not understood as an example of the rise of fascism in America. Instead, Floyd’s murder emboldened the Black Lives Matter movement, which essentially proclaims that Black Americans should be viewed as part of American society’s common people and not as an Other whose lives do not matter or somehow matter less.

In 2026, however, Renée Good and Alex Pretti were killed by American law enforcement in Minneapolis, and their murders are increasingly perceived and understood as an example of American fascism. That’s because these white Americans were part of the “common” people and their murders showed that the federal government could render white Americans the Other, too.

Additionally, Trump’s aggressive deployment of ICE and targeting of Latinos has been perceived as closer to American fascism than attacks against Black Americans. Latinos are not white–even if many Latinos can pass as white–but the United States was not built around the belief that they should be the perpetual Other. The potential to become part of the “common” people is supposed to exist. Kidnapping Latinos, breaking up their families, sending them to detention centers, and deporting them amounts to turning Latinos into the Other. The transition from being potentially part of the “common” people to becoming the Other elicits a trauma that bears a family resemblance to European fascism.

America’s comfort and familiarity with having a perpetual Other makes it much harder for Americans to recognize the symptoms of fascism because Americans are less concerned about the terrorism and more concerned about who is being terrorized. Until the terror impacts white Americans it is often described as spectacle.

Therefore, if we proclaim fascism’s “arrival” today due to the Othering of white Americans, we will never defeat American fascism. To defeat fascism in America, we also have to acknowledge its unnamed presence at the inception of our “democracy.” This can be a hard reality for white Americans to accept, but it is one they must accept if a truly united people are to defeat American fascism.

To defeat American fascism, the United States must do something that it has never done before: Create a common people.

Umberto Eco’s Fourteen Features of Ur-Fascism

The first feature of Ur-Fascism is the cult of tradition. Traditionalism is of course much older than fascism. Not only was it typical of counter-revolutionary Catholic thought after the French revolution, but it was born in the late Hellenistic era, as a reaction to classical Greek rationalism. In the Mediterranean basin, people of different religions (most of them indulgently accepted by the Roman Pantheon) started dreaming of a revelation received at the dawn of human history. This revelation, according to the traditionalist mystique, had remained for a long time concealed under the veil of forgotten languages — in Egyptian hieroglyphs, in the Celtic runes, in the scrolls of the little known religions of Asia.

This new culture had to be syncretistic. Syncretism is not only, as the dictionary says, “the combination of different forms of belief or practice”; such a combination must tolerate contradictions. Each of the original messages contains a silver of wisdom, and whenever they seem to say different or incompatible things it is only because all are alluding, allegorically, to the same primeval truth.

As a consequence, there can be no advancement of learning. Truth has been already spelled out once and for all, and we can only keep interpreting its obscure message.

One has only to look at the syllabus of every fascist movement to find the major traditionalist thinkers. The Nazi gnosis was nourished by traditionalist, syncretistic, occult elements. The most influential theoretical source of the theories of the new Italian right, Julius Evola, merged the Holy Grail with The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, alchemy with the Holy Roman and Germanic Empire. The very fact that the Italian right, in order to show its open-mindedness, recently broadened its syllabus to include works by De Maistre, Guenon, and Gramsci, is a blatant proof of syncretism.

If you browse in the shelves that, in American bookstores, are labeled as New Age, you can find there even Saint Augustine who, as far as I know, was not a fascist. But combining Saint Augustine and Stonehenge — that is a symptom of Ur-Fascism.

Traditionalism implies the rejection of modernism. Both Fascists and Nazis worshiped technology, while traditionalist thinkers usually reject it as a negation of traditional spiritual values. However, even though Nazism was proud of its industrial achievements, its praise of modernism was only the surface of an ideology based upon Blood and Earth (Blut und Boden). The rejection of the modern world was disguised as a rebuttal of the capitalistic way of life, but it mainly concerned the rejection of the Spirit of 1789 (and of 1776, of course). The Enlightenment, the Age of Reason, is seen as the beginning of modern depravity. In this sense Ur-Fascism can be defined as irrationalism.

Irrationalism also depends on the cult of action for action’s sake. Action being beautiful in itself, it must be taken before, or without, any previous reflection. Thinking is a form of emasculation. Therefore culture is suspect insofar as it is identified with critical attitudes. Distrust of the intellectual world has always been a symptom of Ur-Fascism, from Goering’s alleged statement (“When I hear talk of culture I reach for my gun”) to the frequent use of such expressions as “degenerate intellectuals,” “eggheads,” “effete snobs,” “universities are a nest of reds.” The official Fascist intellectuals were mainly engaged in attacking modern culture and the liberal intelligentsia for having betrayed traditional values.

No syncretistic faith can withstand analytical criticism. The critical spirit makes distinctions, and to distinguish is a sign of modernism. In modern culture the scientific community praises disagreement as a way to improve knowledge. For Ur-Fascism, disagreement is treason.

Besides, disagreement is a sign of diversity. Ur-Fascism grows up and seeks for consensus by exploiting and exacerbating the natural fear of difference. The first appeal of a fascist or prematurely fascist movement is an appeal against the intruders. Thus Ur-Fascism is racist by definition.

Ur-Fascism derives from individual or social frustration. That is why one of the most typical features of the historical fascism was the appeal to a frustrated middle class, a class suffering from an economic crisis or feelings of political humiliation, and frightened by the pressure of lower social groups. In our time, when the old “proletarians” are becoming petty bourgeois (and the lumpen are largely excluded from the political scene), the fascism of tomorrow will find its audience in this new majority.

To people who feel deprived of a clear social identity, Ur-Fascism says that their only privilege is the most common one, to be born in the same country. This is the origin of nationalism. Besides, the only ones who can provide an identity to the nation are its enemies. Thus at the root of the Ur-Fascist psychology there is the obsession with a plot, possibly an international one. The followers must feel besieged. The easiest way to solve the plot is the appeal to xenophobia. But the plot must also come from the inside: Jews are usually the best target because they have the advantage of being at the same time inside and outside. In the U.S., a prominent instance of the plot obsession is to be found in Pat Robertson’s The New World Order, but, as we have recently seen, there are many others.

The followers must feel humiliated by the ostentatious wealth and force of their enemies. When I was a boy I was taught to think of Englishmen as the five-meal people. They ate more frequently than the poor but sober Italians. Jews are rich and help each other through a secret web of mutual assistance. However, the followers must be convinced that they can overwhelm the enemies. Thus, by a continuous shifting of rhetorical focus, the enemies are at the same time too strong and too weak. Fascist governments are condemned to lose wars because they are constitutionally incapable of objectively evaluating the force of the enemy.

For Ur-Fascism there is no struggle for life but, rather, life is lived for struggle. Thus pacifism is trafficking with the enemy. It is bad because life is permanent warfare. This, however, brings about an Armageddon complex. Since enemies have to be defeated, there must be a final battle, after which the movement will have control of the world. But such a “final solution” implies a further era of peace, a Golden Age, which contradicts the principle of permanent war. No fascist leader has ever succeeded in solving this predicament.

Elitism is a typical aspect of any reactionary ideology, insofar as it is fundamentally aristocratic, and aristocratic and militaristic elitism cruelly implies contempt for the weak. Ur-Fascism can only advocate a popular elitism. Every citizen belongs to the best people of the world, the members of the party are the best among the citizens, every citizen can (or ought to) become a member of the party. But there cannot be patricians without plebeians. In fact, the Leader, knowing that his power was not delegated to him democratically but was conquered by force, also knows that his force is based upon the weakness of the masses; they are so weak as to need and deserve a ruler. Since the group is hierarchically organized (according to a military model), every subordinate leader despises his own underlings, and each of them despises his inferiors. This reinforces the sense of mass elitism.

In such a perspective everybody is educated to become a hero. In every mythology the hero is an exceptional being, but in Ur-Fascist ideology, heroism is the norm. This cult of heroism is strictly linked with the cult of death. It is not by chance that a motto of the Falangists was Viva la Muerte (in English it should be translated as “Long Live Death!”). In non-fascist societies, the lay public is told that death is unpleasant but must be faced with dignity; believers are told that it is the painful way to reach a supernatural happiness. By contrast, the Ur-Fascist hero craves heroic death, advertised as the best reward for a heroic life. The Ur-Fascist hero is impatient to die. In his impatience, he more frequently sends other people to death.

Since both permanent war and heroism are difficult games to play, the Ur-Fascist transfers his will to power to sexual matters. This is the origin of machismo (which implies both disdain for women and intolerance and condemnation of nonstandard sexual habits, from chastity to homosexuality). Since even sex is a difficult game to play, the Ur-Fascist hero tends to play with weapons — doing so becomes an ersatz phallic exercise.

Ur-Fascism is based upon a selective populism, a qualitative populism, one might say. In a democracy, the citizens have individual rights, but the citizens in their entirety have a political impact only from a quantitative point of view — one follows the decisions of the majority. For Ur-Fascism, however, individuals as individuals have no rights, and the People is conceived as a quality, a monolithic entity expressing the Common Will. Since no large quantity of human beings can have a common will, the Leader pretends to be their interpreter. Having lost their power of delegation, citizens do not act; they are only called on to play the role of the People. Thus the People is only a theatrical fiction. To have a good instance of qualitative populism we no longer need the Piazza Venezia in Rome or the Nuremberg Stadium. There is in our future a TV or Internet populism, in which the emotional response of a selected group of citizens can be presented and accepted as the Voice of the People.

Because of its qualitative populism Ur-Fascism must be against “rotten” parliamentary governments. One of the first sentences uttered by Mussolini in the Italian parliament was “I could have transformed this deaf and gloomy place into a bivouac for my maniples” — “maniples” being a subdivision of the traditional Roman legion. As a matter of fact, he immediately found better housing for his maniples, but a little later he liquidated the parliament. Wherever a politician casts doubt on the legitimacy of a parliament because it no longer represents the Voice of the People, we can smell Ur-Fascism.

Ur-Fascism speaks Newspeak. Newspeak was invented by Orwell, in 1984, as the official language of Ingsoc, English Socialism. But elements of Ur-Fascism are common to different forms of dictatorship. All the Nazi or Fascist schoolbooks made use of an impoverished vocabulary, and an elementary syntax, in order to limit the instruments for complex and critical reasoning. But we must be ready to identify other kinds of Newspeak, even if they take the apparently innocent form of a popular talk show.

Thanks for this brilliant explanation of Fascism, Barrett. And yes, if only Americans would finally acknowledge the errors/sins/fallacies of our culture, we might be able to move forward into a reality that truly does include everyone...

Fascism as #MadeInAmerica