Confronting History & Reconstructing America Through Cinema and Culture

Part 2 of our conversation with philosopher Barrett Holmes Pitner about Ryan Coogler's latest film "Sinners"

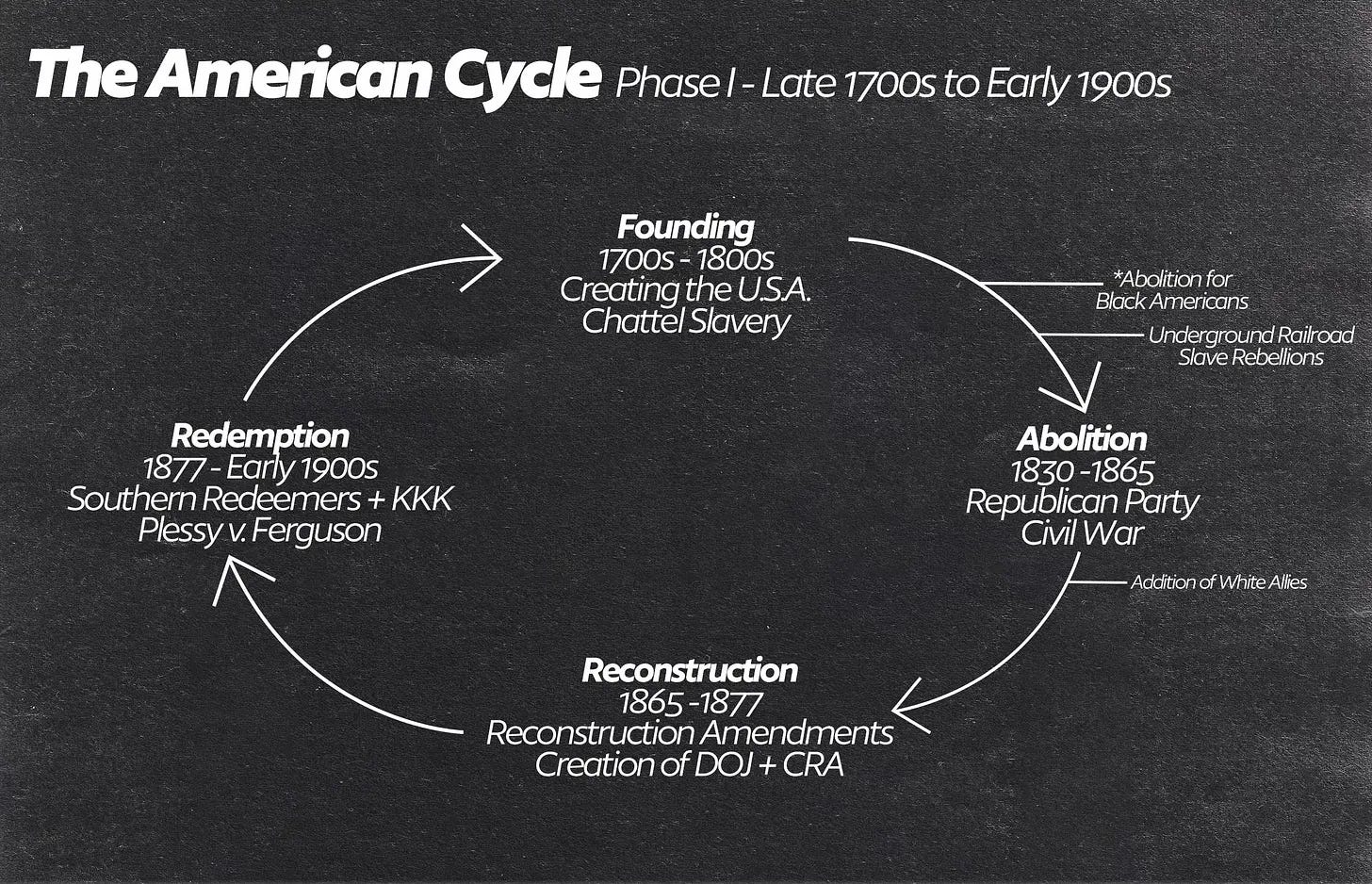

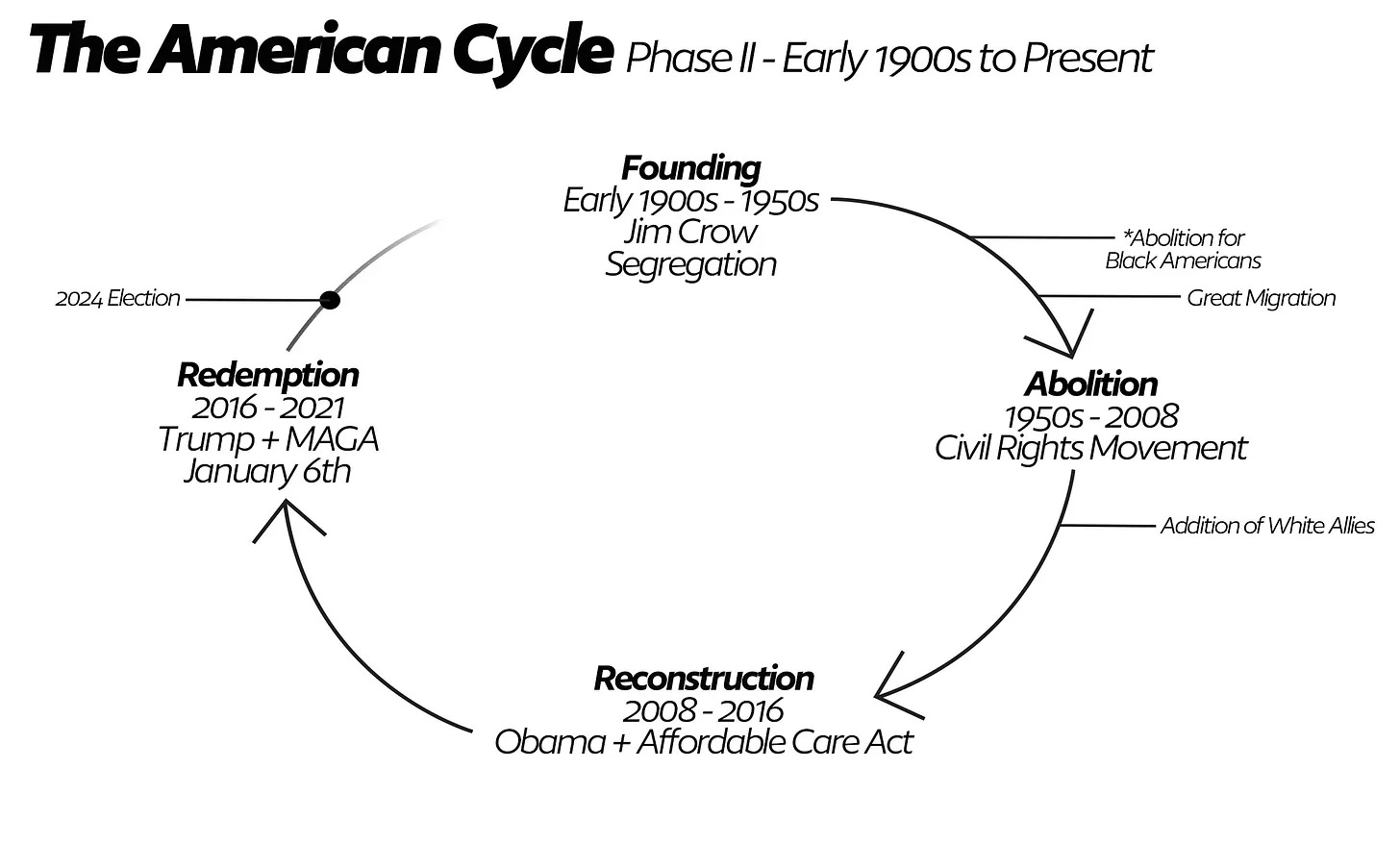

When Barrett and I pressed record on our conversation, I don’t think we realized how much we would have to say about the film Sinners (2025). As we were in the editing process, we decided to break the interview into two parts. Part one contains a lot of our initial thoughts about the film, its significance, and why we both think it’s such an incredible film. Barrett also talked about the American Cycle as well and how films like The Birth of a Nation and now Sinners play an important role in shaping not just culture but policy and history. Part 2 of our conversation picks up where Part 1 left off.

We spoke via Zoom; he in Washington D.C., I in Los Angeles. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

JSC: So as we were talking about policy and the political side of of the second Founding Era in the early 20th century, I’m also thinking about how the film The Birth of a Nation was a huge cultural moment in terms of storytelling being a medium for affirming the things that were happening in the political and social spheres. You mentioned that the Trump era right now is a Redemption Era. The Birth of a Nation comes out during the First Redemption Era, launches the Second Founding, and then, in this current moment of the Second Redemption Era, Sinners comes out. What are some of the differences between the First Redemption and the Second for you? Some of the differences that I see are that there are so many more Black people in positions of power, with money, than in that first Redemption. I’m curious what you think about some of those, because I think it'd be easy for someone to hear about the cycles and assume that we're going back into a new Founding Era that's going to look exactly like the first two. You talk about how we have to fight for Reconstruction now, and so I’m wondering if this movie fights for Reconstruction by telling the truth, and showing us the reality versus telling us these lies and these myths about the “Lost Cause,” slavery being a good thing and Black people needing to be controlled by systems and, groups like the Klan.

BHP: So that's a very good question. The reason The Birth of a Nation was able to resonate so culturally is that the American Right and all the various racist groups know what their origin is. They have a real clarity and are trying to celebrate this part of American history. So when The Birth of a Nation is coming out in 1915 and it's celebrating the narrative of white supremacy and of Black people being subhuman, there is no ambiguity within the American cultural landscape about the accuracy of that. And there’s a history of policies and language advocating for how that is the natural order for us to live. They can get this movie, and they can run with it. It already fits within the template that they've set for how they want to live in the world.

The Left struggles with the fact that they don’t really know what their origin story is. There can be a film in Sinners that is a visceral expression of the Left’s true origin story, that they can grab and run with it, like the Redeemers and creators of Jim Crow did in 1915. But since the Left doesn't know their origin story, that opportunity could easily slide away. They'll just see it as entertainment.

The Left struggles with the fact that

they don’t really know what their origin story is.

- Barrett Holmes Pitner

The origin story for anybody in America who cares about equality and multiracial democracy is Reconstruction. That's it. Equality and multiracial democracy didn’t exist before Reconstruction. The narrative of the 1960s of Civil Rights and Roe, Loving v. Virginia, none of that could have been possible without Reconstruction. Yet the American Left will look at the Civil Rights era as their origin story. And that's an era about abolishing the bad. Reconstruction is about creating the good after you've abolished the bad.

If you're going to create good stuff, some of that stuff is going to be cinema. It’s going to be art. If you're not accustomed to knowing how to create good things or the unifying origin story, someone can try to create that good thing off of vibes and you won't even know that it's part of your cultural fabric. Not like Black cultural fabric, but just like your multiracial American cultural fabric. That is Reconstructionism.

That's why fighting for Reconstruction is so important.

And so with this film, I feel that if people are willing to become Reconstructionists, they'll see the film as a vehicle to champion, because it's part of that Reconstructing. The film will add another layer of depth. Not only is it a great experience to go to the cinema and see it, but it provokes all sorts of questions, and you can take it to a whole new philosophical level.

You can take it to a level of where it influences certain policies, just like The Birth of a Nation did, because they recognized their origin story when they saw it. Once the Left knows their origin, I think it will be sorted.

JSC: You mentioned that the Right knows its story, where it comes from. If the Left is missing a story, are you saying that Sinners could be one of those stories, if not the story that the Left goes with for now as its origin story? Is that what I'm hearing you say?

BHP: For the Left, a hundred percent.

JSC: So, tell me more about the way you specifically see this film. If people don’t see this as an origin story, what are some of the specific ways it could affect policy, philosophy, culture, etc?

BHP: So there are so many. Let's just take the example of the core basis of the movie without any of the vampire stuff. We have two brothers whose father was abusive, probably because he's lived a traumatic life as a Black man in America. These guys, clearly smart people, had to turn to a life of crime. Then, even though they engaged in that crime up north, their goal was still to use that money for the benefit of the Black community. They came back and they wanted to use that money to build something for Black people to be able to form community. And they're cool. And they aren’t racist. <Laugh> Asian people were there, there was a white passing Black lady there, so it's a multicultural thing.

And we know that the white people who took their money for the property on the premise of an authentic transaction were planning on taking their money and then killing them. This is not a far-fetched idea. So if we're talking about policy, this is just like consumer protections. We're talking about the need for education, healing of inter-generational trauma, and all the aspects of a person's life to make them stable. You can see that just this little component is showing that people in this country have tried to make Black existence unstable and almost impossible to thrive and grow. If you object to that type of oppression, we are now having some really serious conversations about policies. We need to counter that this normalized division and oppression.

What happens a lot, and the Supreme Court’s conservative justices will always make these arguments that America has progressed beyond these racial horrors. That we just need to get past it and therefore don't need to have anything pertaining to race or this, that, and the other. But Ryan Coogler wrote this because his uncle, who he said helped raise him to a significant degree, loved Buddy Guy and Buddy Guy's in the movie. So like, the history that’s being depicted in the film isn't that far back. The people that made Black Panther are being influenced by the people who were living in the 1930s. Coogler likes blues, you know? There's a clear conduit to it. There's not a line of demarcation where history just ended and we started anew. An ahistorical way of living is not going to help us make policies.

Another thing you hear them talk about in the movie is how they know each other, you know, like they're cousins. They know everybody. That's a clear narrative for the benefit of multi-generational living. Start giving tax breaks to people who want to have multi-generational homes. Maybe encourage businesses or housing construction to make those types of houses for that type of living, because a lot of people live that way. The reason that they weren't able to live in that communal, multi-generational way was because people were going in there and actively trying to destroy their way of being and traumatizing people. And now they have to leave in order to escape trauma. Like, that's just right there in the movie. And so once you start thinking at a higher level and recognizing the roots of where this America that we live in comes from, you can then start seeing stuff at a better level. The film could clearly be taken to another level after that.

JSC: I agree with you. So we were texting each other about one scene in particular, the scene everyone really is talking about, which is not the vampire siege attack by the way, but the surreal musical scene that's at the center of the heart of the movie. We both said it was an amazing scene. I said it was one of the most important scenes in film history. I'm curious how you saw that scene and how it fits into this Reconstructionist effort and, and even how what you just shared about could be learned from this scene moving forward as an origin story.

BHP: It's definitely one of the most important scenes in cinematic history. It's up there. That's also a scene that's magic realism. And that magic is the soul of a people, both backwards and forwards. And so, one of the reasons I think the Latin American community has magical realism at the forefront is that they're closer to an indigenous culture, you know? And like in the Americas, the Haudenosaunee have a practice called the Seven Generations Principle, which says, in all of your actions, you should think about the impact of those actions seven generations into the past and seven generations into the future. And so just interacting with a person, us hanging out right now for example, the idea guiding how I interact with you should be shaped by seven generations into the past. And hopefully, that would allow us to be friends for seven generations in the future. So like, our kids would be friends.

JSC: Right, I agree.

BHP: This is something that's completely lost to the West. For people of color, though, it's there to a latent extent where we have to express it artistically. And that scene illustrates how there's been a desire to destroy our spirit, our geist, through ethnocide. And so even though as a Black American person, I know that if I meet an African person, we can get along to a certain level, but culturally, there's going to be something different. My connection to Africa will be much, much less, but it has not been completely erased, and that latent connection has also manifested into a uniquely Black American expression.

And so having that expressed through music and rhythm and dance is significant. It shows the presence of a thing that we kind of all know is there to a latent extent. We just don't know how we activate it to a certain extent. There's a question about how do we authentically activate it? And then you realize that we've been activating that little bit that we have to the best of our ability through music. And these people in this environment sing in the Blues, which is a genre that's built on the terror created by colonizers, is also an expression of our kind of latent African spirit.

That tells a pretty vibrant story. I think America and the West like people to exist as alienated people who believe that they live as individuals forever. Where people say crazy stuff like, “you're born alone, you'll die alone.” But the truth is that you aren't born alone. Like you literally come out of a person. When my kid was born, I was there and there were a bunch of people there. So, he was not born alone. Does he know the names of all those people? No. Do I know their names? Of course not. But there were a bunch of people there. For us to even think it makes sense to articulate something like, “you're born alone and you'll die alone,” is just a way of professing an alienated way of living. Which I think the West projected on everybody. Their individualism is a delusion, but so is their belief that the beyond or the afterlife is more important than life. I could talk about these delusions all day, but maybe that should be for another interview.

This fight between wanting to let go of the delusion and embrace reality defines the West. If you can delude yourself into thinking that everything comes from beyond existence, then you can say, “Oh, I'm born alone,” even though you literally come out of a person. It makes no sense. And I think the West spends a lot of time trying to convince other people who have come from completely different philosophical traditions, from different continents, that they also need to be as alienated as the West is. That's also why I think that it is very significant that they picked vampires. I think a lot of European myths and horror stories are an expression of this alienation and how it consumes them, but they can't really escape it.

JSC: You texted me a tweet a couple of days after we initially said we were going to talk. In the first part of the tweet, a woman, visibly white from their avatar says, “I don't know if Ryan Coogler intended this (though I feel like he must have on some level), but Sinners left me with a real sense of grief over the disconnect I feel from my cultural heritage. I'm a white American, and I have no idea where I came from. I have no cultural roots to draw from; my past is just empty.” The response to that tweet by a woman whose avatar is visibly Black is: ”So you ain't see the Klan in the movie?” :

I was curious what this tweet says to you?

BHP: Yeah. So yeah, it speaks to the alienation that's at the root of all of it. When I talk to people about ethnocide, and I tell them what it is, what will end up happening at some point is some white American will describe what that tweet describes. They have a similar sentiment where, at some point they were German or French or this thing or that thing, and now they're just white. And there's like an emptiness to that, according to them, you know? And I'm like, well, if your culture makes an argument that it's beneficial to destroy somebody else's culture in exchange for money, then why wouldn't it make sense for them to destroy their own culture in exchange for money as well? If you were Italian, or you know, French or whatever, I don't know, someplace in Europe, and you come over here and you find out that it's hard to make money with an Italian last name or something, you then spend a whole bunch of time making yourself into this commodified, soulless, culture-less white person because you feel you'll recoup more money that way.

And our whole society is based on that. Everyone does it. It's just assimilation as we say it here. As Black people, we can't assimilate to that degree. And so we always just have to end up trying to keep our own spirit, because the premise for the transaction, we can't do it. We can't ever look white enough to go full in. And so this white woman who is saying that she feels like her culture is nothing is saying this because she's done the transaction.

But that nothingness that she is describing doesn't start at nothingness. It doesn’t start as a culture of nothingness. It starts with a group of people committing themselves to terrorizing other people. And there you go.

And so I think one of the things that the West often likes to do, and clearly, if you have the power, you're going to create a narrative that erases all the horrors that you've done. And so they'll create a narrative like The Birth of a Nation, where the horrors, the mass killing and all that stuff are just not focused on, and we just talk about all these good things. It's a bad-faith, dishonest telling of history. And so this white person can look at Sinners and see all the white people and all the Klan people and not notice that none of the Klan people are wearing the Klan outfits.

JSC: The white man they buy the barn from at the beginning of the film literally says in the film that the Klan doesn't exist anymore, which is a bad faith statement. And if you notice, the brothers kind of just smile, and the film just kind of fades into the next scene. But that’s what it's pointing out.

BHP: Right. And so the person from the tweet can look at all these white people and see all that terror and be like, “I'm not a part of that. My whiteness is the kind of whiteness that's ‘nothing.’” And it's like, no, no, no. That nothingness that you feel, is because they've erased the horror. If they told you all the horrors, you probably wouldn't want to engage in the transaction.

JSC: And then what?

BHP: Exactly. If you were Irish and you came over to America, and it's like, all right, there's a type of white people in America in the Jim Crow South who just collectively gather and go and terrorize people of color all day long. And they're never going to get punished. They control the police, and they control everything. They just terrorize people all the time. And they're planning on doing this forever, for a thousand years.

When you move here, if you want to be successful, you need to mold yourself so that you fit in with them. Like, that pitch isn't going to be that appealing <laugh>, but they say, “Hey, you come over here and it’s a land of opportunity. You're going to get a job, you're going to get money, if you just work hard.” That's the whole narrative. But, you know it's a lie.

And so this person that's white, she could see the distinct American iteration of whiteness that, like linguistically, she's clearly a part of. Those are white people in the movie. She's a white person. There's not a point where it's like, ah, these are different white people. No, they're just white people. And she thinks, “Ah, I'm not that, I'm another thing.” When I saw that tweet, I thought about this white person, and thought, “You come from that thing, like you as a person right now, you very well are most likely not racist and don't do any of that stuff. But, that's just because you've progressed. That's not because you aren't from that culture. And so that's a hard pill to swallow.

JSC: It is a hard pill to swallow. I'm thinking about myself watching the film and seeing that central musical scene. It was very emotional for me. I was tearing up the second time I saw it because I was shocked by it the first time. I didn't even know what to think. I knew what to expect the second time. But if you're somebody who is white and who is, is having the experience described by the tweet and wants to maybe even swallow that pill, how does one do that? Because it's one thing to say, “Oh, I can feel so energized and proud of seeing my lineage portrayed on screen in this way, where we’re cultural builders and makers, you know, things like that.” If their lineage is what you said about terror and extraction and a kind of vampiric undeadness, how does one swallow that? Or what is, how does one swallow that pill? And what's the path forward with it?

BHP: So this is where we're talking about Reconstructionism in a really profound, implementation way. It’s not like talking about policy. If you are alone or you're just an individual that's detached and alienated from anything and everything, everything is hard to do. You know, <laugh> like everything becomes really hard if you're alone and just an individual and you have to do everything by yourself. You're born alone, you die alone. So that trauma for that person is like, how do I deal with this by myself? And that makes it really, really hard. And the answer is, if you're doing it that way, you'll never deal with it. You're always just going to suffer forever.

But in a Reconstructionist framework, a society that actually cares about having a sustainable, nurturing culture, you deal with that trauma as a community. Now, the complexity, and if you look at the movie, I think the movie does a good job of showing that the Black community was not exclusionary <laugh>. He went to the Chinese grocery store and they treated each other like people. Cool. Come on in, that kind of thing. I think one of the parts that made me tear up was just the genuine expression of love that both of Michael B. Jordan's characters had for their respective women. Like that was a very authentic expression. And they're two completely different-looking women, you know, like with Mary, Smoke chose not to interact with her, told her to go away because he wanted her to have a better life because society wouldn't allow it to happen. If society had allowed it to happen, he would have been with her forever.

JSC: Which, in the end, he ends up doing.

BHP: Exactly. And so, like that community where these white people can deal with that trauma is not going to be a community white people are going to create, because philosophically they've been taught not to create community that way. Their communities are very individualistic, transactional communities. People of color create different communities.

JSC: There’s that flashback scene at the end where it shows them coming together, the truck backing in, shelling peas, you know, frying the fish. That is essentially what you're advocating for. That's community on screen, you know? As a response to the systems of oppression.

BHP: Right. Reconstruction as an era in America was like the first time that America tried to make that community at scale. And so the thing that makes it very complicated is that the length of America and the [divisive, individualistic] philosophy that guides it make it logical that when a white person says, “Open the door and let me in. You can trust me. I think you can help me deal with my trauma.” Well, we're going to be skeptical. That's just logical, you know?

But the way for that white person to deal with that trauma of seeing her culture, for what it is; Black culture, Black community, communities of color, will probably be the best place to help them deal with that trauma because we're not as individualistic at a philosophical level.

JSC: We couldn’t afford to be.

BHP: Exactly. We just couldn't afford to be, it's a completely different construct.

JSC: I think that's one of the philosophical underpinnings of the film. We have to have each other's backs.

BHP: Right. And so this white woman, who is really shocked and doesn't know how to deal with the emotions of this movie, wants someone to help her cope with this, and the person to help her cope with this is Ryan Coogler. <Laugh>.

JSC: Right. I think this is a good moment to end on, do you have anything that I haven't brought up that you want to talk about, regarding the movie?

BHP: I think I wanted to mention the vampire stuff because vampires, Frankenstein, all that stuff is from an alienated culture, and those are the myths that they make. Vampires are alienated from humanity and can only survive by devouring the blood or life force of other humans. When they become vampires they are severed from their community and culture, but they can live forever so long as they continue to consume other people. This is consumption and the destruction of geist. Also, they can’t exist in the light and must live in darkness. If they remain unenlightened and live to consume, they can live in darkness for eternity. I think Westerners created the myth of the vampire because it is an expression of their culture. I thought that was a very apt choice, choosing vampires.

It's just one of the best movies ever made.

And it, frankly, it's when you said it felt Reconstructionist to you, I felt that that might be one of the best compliments I've ever gotten. Someone says my work could be on par with what I think could be one of the greatest movies ever. That's great. That's pretty cool.

JSC: Yeah. And I think it's the movie we need as a model of what, like you said, what to do, how to respond.

BHP: Yes. It's a cultural expression. And yeah, I guess one last thing to mention is my organization The Sustainable Cultural Lab. It's a cultural think tank. I think that if we are trying to change our society for the better, cultural expression is a key component. That's art and music and all that stuff in addition to policy and voting and things like that. Yeah. And so this film is definitely a cultural expression of the geist or a zeitgeist of our time.