Then and Now: The Elections that Halted Reconstruction

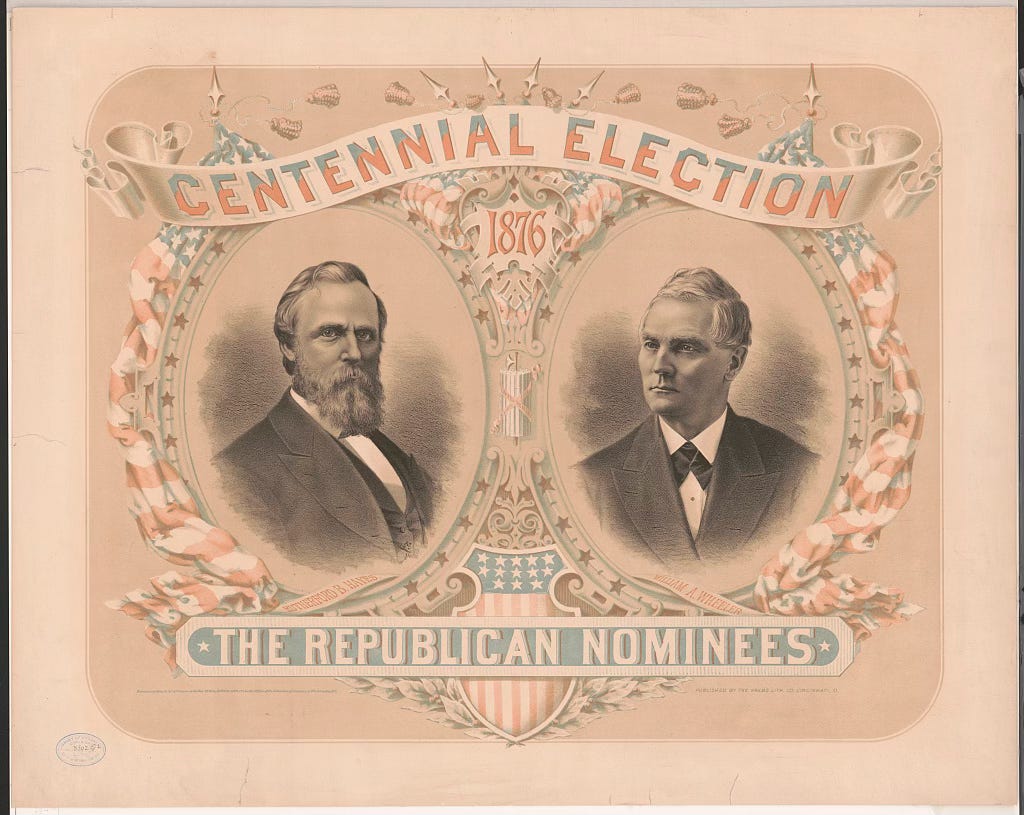

The election of 1876 marked the end of Reconstruction and ushered in an era of racial oppression and disenfranchisement of Black Americans known as the Redemption era. By examining what led to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes’ victory against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden in this highly contested election, we can gain valuable insight into the cyclical nature of American politics and the importance of the 2024 election in determining whether we continue the work of Reconstruction or allow regression to persist.

Immediately following the Civil War, Reconstruction was at the heart of the 1876 election. Tilden, the governor of New York, appealed to white Redeemers who wanted to see a South restored to its pre-war glory, white supremacy included. Hayes, a Civil War veteran and governor of Ohio, dedicated himself to resolving divisions left behind by the war and protecting the rights of newly emancipated Black Americans.

One of the defining features of the 1876 election was the widespread disenfranchisement of Black Republican voters in the South. In an effort to prevent the extension of civil and political rights to Black Americans by a new Republican government, Southern Democrats sought to suppress the Black vote through organized threats of violence and intimidation by such white supremacist paramilitary groups as the Red Shirts and White League.

This strategy was designed in accordance with what is known as the Mississippi Plan. Devised in 1874, the Mississippi Plan aimed to prevent Republicans from taking power in the South and, in 1890, resulted in a new Mississippi state constitution with stricter voter registration laws that would remain in force until the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

This disenfranchisement, in combination with allegations of voter fraud across the South, resulted in an election in which Tilden won the popular vote but did not receive a majority of the electoral college votes needed to officially secure the presidency. Electoral vote disputes centered around four states—Florida, Louisiana, Oregon, and South Carolina. Florida and Louisiana had reported a win for Tilden; Hayes won South Carolina, and, in Oregon, the vote of a single elector was undetermined.

Had it not been for the Democrat-led voter suppression campaign that swept the South during the election, Hayes would have undoubtedly been declared the legitimate winner. However, with no clear guidance from the Constitution, and with inauguration day approaching, a 15-person Electoral Commission was established to settle the dispute.

The commission was made up of eight Republicans and seven Democrats who voted along party lines to certify that Hayes had won the disputed votes. But his victory did not come without a cost. To take effect, the Electoral Commission’s decision had to pass through the Democrat-controlled House of Representatives, which planned to filibuster to prevent Hayes from taking office.

To get around this roadblock, Republican supporters of Hayes and moderate Democrats came together in the so-called Compromise of 1877. Despite there being no written evidence that such a compromise was reached, it is widely believed that the deal both ended the filibuster and stipulated that the last federal troops be removed from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction.

When federal troops left the South, so did many white Republicans, leaving Redeemers, who already dominated Southern government, in control. The compromise represented a betrayal of the principles of equality and justice upon which Reconstruction had been founded and paved the way for decades of racial oppression and discrimination. Black Americans’ civil rights were once again at risk as the U.S. began what would become the first Redemption era, marked by Jim Crow laws and the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan across the South.

As the 2024 election approaches, the lessons of history are clear: when we fail to confront the forces of bigotry and hatred, we risk repeating the mistakes of the past. Trump’s election in 2016 was the beginning of a second Redemption era—a clear regression of the progress made under the Obama administration and a resurgence of white supremacist ideology. Trump’s presidency emboldened those who sought to roll back the gains of the Civil Rights Movement and stoked divisions along racial and ethnic lines.

Similar to the election of 1876, the 2016 election was also only the fifth time in U.S. history that a president-elect did not win the popular vote.

In 2020, despite increased partisanship and baseless allegations of voter fraud from Trump and his allies (Ted Cruz even called for the creation of a modern-day Electoral Commission), Biden won. Beginning with his historic nomination of Kamala Harris as Vice President, Biden pledged his commitment to advancing civil rights and fighting systemic injustice, continuing the legacy of Reconstruction and the unfinished work of the Civil Rights Movement.

By contrast, Trump’s embrace of white supremacist rhetoric and his attempts to undermine the legitimacy of democratic institutions posed, and continues to pose, a direct threat to the values that define our nation. A second Trump presidency would not only reverse the progress achieved during Reconstruction but also empower those who aim to prolong the American Cycle of racial oppression and division.

Now, as Biden seeks reelection and Trump runs for a second term, Americans have a stark choice to make. The 1876 election should serve as a vivid reminder of the consequences of complacency and compromise in the face of injustice.