Then and Now: The American Cycle and Prosecuting White Terrorism

The United States’ propensity for reducing punishments for acts of white terrorism has revealed our alarming cycle of regression within the American legal system that diminishes the accountability of white individuals and their role in endangering our democracy.

This trend has been evident in the handling of cases involving the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) from the 1800s to the present-day defendants from the Jan. 6, 2021 Insurrection.

From 1871-1872, the newly formed Department of Justice (DOJ) assumed responsibility for protecting the rights of freedmen by prosecuting KKK members across the South. The 14th Amendment provided equal protection to all American citizens, including the freedmen community, while the 15th Amendment granted Black men the right to vote. These advancements posed a threat to white supremacy, prompting the KKK to intimidate politicians and Black voters at polling stations, conspire against them, and carry out violent attacks across the South to suppress their vote and challenge the constitutional authority of these amendments.

In the 1800s, the KKK and other white supremacist militias formed alliances with Southern Democrat politicians to reclaim control of the South through both violence and the ballot box. This alliance of white supremacist militias and politicians called themselves “redeemers” and their mission was to “redeem” the South by destroying Reconstruction and returning the South to a pre-Civil War, antebellum status quo.

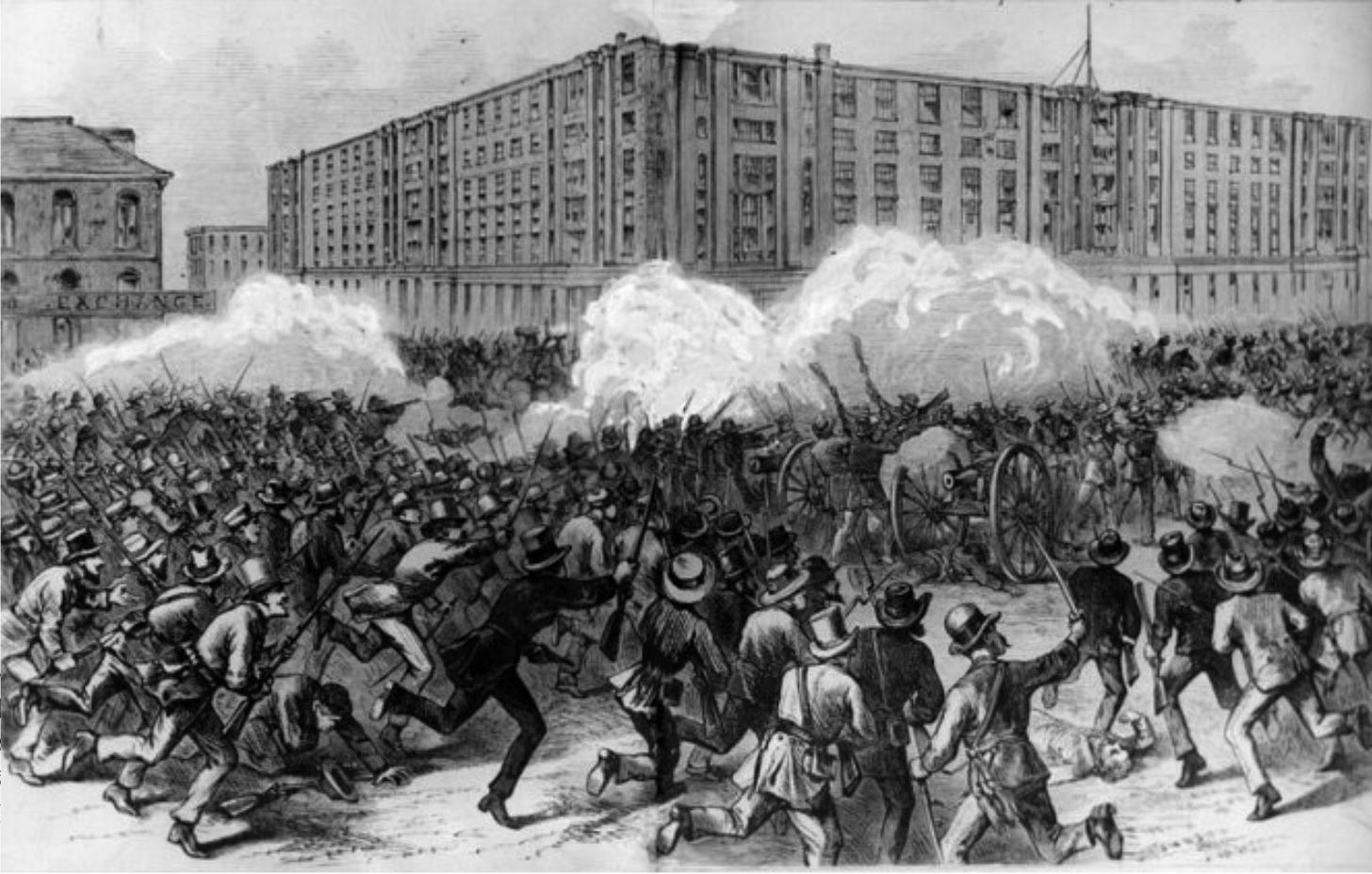

In 1873 and 1874, redeemers in Louisiana, consisting of both politicians and white supremacist militias, challenged the legitimacy of the state’s gubernatorial election, and stormed the state’s seat of government. In the 1873 coup, the racially integrated police force in New Orleans defeated the white terrorists, but the second attempt in 1874 defeated the police and the terrorists temporarily seized control of the state until federal troops were sent down and defeated them. Despite the perpetrators of the attacks being known, very few were prosecuted.

The redeemers of the 1860s and 1870s were the precursors and regional iteration of Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement. Both movements espoused a message harkening to a “better” America that was less equitable and dominated by white men, they formed alliances between politicians and white supremacist militias, and they were willing to use force to seize control of the government. Same agenda, but 150 years apart.

In the 1870s, Attorney General Amos T. Akerman, who oversaw the DOJ, and David Corbin took note of the KKK’s violence and acknowledged the urgency to protect both the constitutional right to vote and the newly emancipated Black American population from white terrorism.

Akerman and Corbin’s legal approach entailed charging individuals with conspiracy to deprive others of their civil right to vote, which would be a violation of the 14th Amendment, in addition to prosecuting state offenses such as murder, assault, and robbery committed while obstructing voting rights. The equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment was created to ensure that the rights of Black Americans received the same protections as those of white Americans. The KKK's terrorism made it imperative for the government, at a federal level, to safeguard the right to vote, as it is the foundation of a healthy democracy.

On the other hand, the attorneys for the KKK members argued that equal protection laws do not constitute new federal crimes and that the DOJ had no authority to utilize equal protection since they claimed that it was the state’s responsibility to do so. Judges Hugh Lennox Bond and George S. Bryan presided over the cases and ruled that Akerman and Corbin lacked the authority to combine state-level crimes with federal conspiracy charges.

By aligning with the Klan’s defense, the verdict concluded that the DOJ had exceeded its constitutional authority, limiting its ability to prosecute Klansmen solely on conspiracy charges. Consequently, prosecutions for crimes like murder and other acts of violence were moved to state jurisdictions, undermining the efficacy of equal protection. By the 1870s, many Democrat politicians who were either former Confederates or Confederate sympathizers had obtained prominent positions at the state and local levels, and steadfastly opposed prosecuting KKK members and other white supremacists. This resulted in the resentencing of several Klan members, whose sentences were reduced as charges such as murder were omitted, leaving them solely convicted on conspiracy charges.

Using violence as an attempt to control and limit political power is not new. On Jan. 6, the cycle continued as the United States Capitol was attacked by a mob of Trump supporters in an effort to overturn President Joe Biden’s rightful win in the 2020 election. The attack led to 140 injured police officers and 5 fatalities. Evidence has emerged demonstrating Trump’s efforts to overturn the election results, including pressuring the DOJ, urging Vice President Mike Pence to nullify the results, and urging Georgia officials to “find” additional Republican votes.

Many of those who have been sentenced for their participation in Jan. 6 for felony obstruction have pursued successful appeals. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit overturned sentencing enhancements used on the defendants, potentially leading to resentencing for all rioters who were charged. Such is seen in the case of retired Air Force Lt. Col. Larry R. Brock Jr, whose conviction was not overturned but instead reduced when the appellate court considered that the previous decision of facing a stricter sentence was not appropriate. These enhancements were based on “interference with the administration of justice,” which the Court of Appeals deemed inapplicable to the crimes at the Capitol. However, the Court upheld the convictions related to halting Congress’s certification of the electoral count. It is yet to be seen how this appeals court decision will impact other convictions as it is based on the judge’s discretion, but the appeal itself will still require a thorough reconsideration of a sentence. This opportunity to be reconsidered shows how language within sentencing policies can undermine the security of our democracy.

Also, the DOJ’s slow investigation of Trump and the events of Jan. 6 further exemplify the inadequate efforts of holding these domestic terrorists, who undermine the Constitution accountable, and this reality is extremely problematic because holding them accountable has been a fundamental principle of the DOJ since its creation in 1870.

The DOJ began in 2021 by indicting the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers, reminiscent of the KKK, due to their extensive contribution to the riot against the Capitol. This is the Department’s largest investigation to date, and they were able to convict prominent members of both militia groups of seditious conspiracy, which is the less serious sister charge of treason. The crime of seditious conspiracy was created in 1861 during the Civil War as a means of punishing Confederates.

However, with Trump practically securing the Republican presidential nomination and the Supreme Court preparing for hearings on his claims of presidential immunity, the 2024 elections will likely happen before Trump’s guilt can be established in court. The DOJ’s struggle to expedite prosecutions, which are especially crucial before the presidential election, combined with recent appeal decisions reducing sentences for insurrectionists, continues an alarming trend of minimizing the punishments of white terrorist organizations and their members, and the white Americans who attempt to overthrow the government.

As seen in the American Cycle, periods of significant progress in preserving democracy are followed by redemption/regression efforts to maintain a political framework that perpetuates inequality. Both the trials involving the KKK and those related to the events of Jan. 6 illustrate the limitations within sentencing policies that diminish the accountability of white Americans for their destructive actions. Rather than making every effort to ensure appropriate punishment is upheld, only minimal measures are often applied.

The decisions made by the courts in the 1870s and 2020s mirror each other. In the 1800s, attempts to enhance conspiracy charges by linking them to murder charges are considered an overreach. Similarly today, charges of interfering with Congress alongside allegations of obstructing justice constitute another overreach that could get sentences reduced. It is becoming more and more evident that tough-on-crime policies often have no place in situations where white Americans violate the Constitution.

Ironically, the KKK terrorists and Trump insurrectionists who advocate for protecting American values and the Constitution are the same individuals who pose the greatest threat to it.