The Forgotten Prosecutions of the KKK & The Former Confederate Who Put Them Away

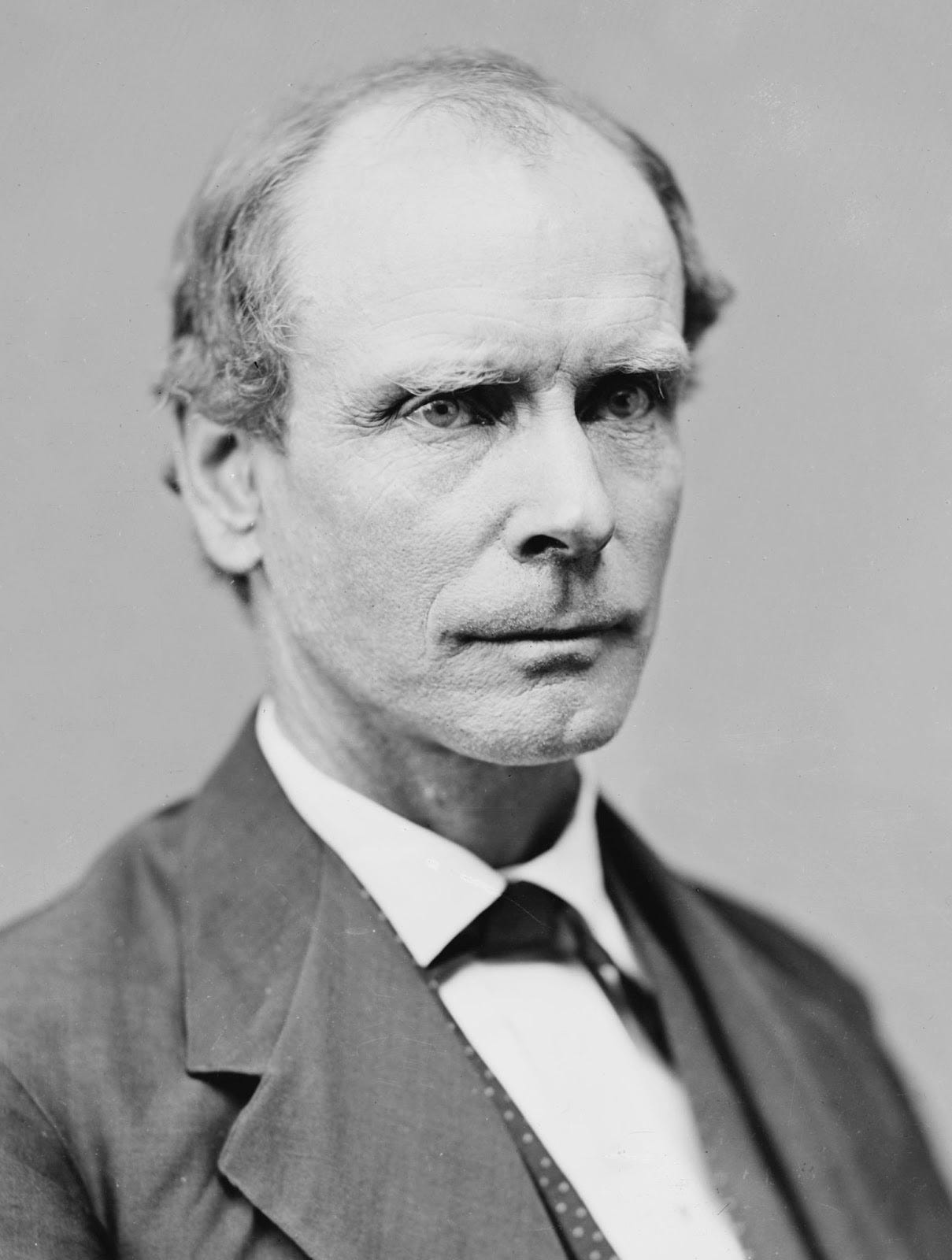

Amos T. Akerman, the Attorney General who initiated the prosecution of the KKK during the start of the DOJ, dismantled the terrorist organization by employing the Enforcement Acts.

The Reconstruction Era undoubtedly generated monumental changes for civil rights, from the developments of the Reconstruction Amendments and Enforcement Acts to the expansion of opportunities for Black Americans from the Freedmen's Bureau. Emerging from the devastation of war, there was a glimmer of hope after centuries of enslavement.

But the progress of this era was repeatedly undermined as the creation of the Ku Klux Klan brought terror and violence. Starting as a small group of Confederate veterans in Tennessee, the Klan grew into a terrorist organization that spread across all of the former Confederate states, committed to ending Reconstruction. Leaving behind burned churches and murdering innocents, their political influence grew from evoking extreme fear. Terrorism and voter suppression became their tactics to undermine the transformative changes initiated by Reconstruction that would hopefully end White supremacy.

By 1868, attacks on Black Americans and the Republican party who led Reconstruction in the South became routine occurrences. All while these crimes were being committed, Black Americans were de facto unable to bring their cases to state courts, where the prosecution of White Klan members was thoroughly and dangerously ignored. Local southern legislatures who ideologically supported the institution of slavery and the oppression of Black Americans found themselves disinterested in taking action on the crimes towards those they viewed as inferior. It was not until the Department of Justice was formed in 1870 that Attorney General Amos T. Akerman took it upon himself to utilize federal authority to eliminate the terror. He took action against the terrorism that gravely violated the 15th Amendment, which granted African Americans the right to vote.

Who is Amos T. Akerman?

Born in New Hampshire in 1821, Akerman led a steady, apolitical life. He focused more on his educational pursuits and was not involved in political affairs. Once he graduated in 1842 from Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, he moved to North Carolina and then further south to Georgia. In Georgia, he tutored the children of Senator John Macpherson and developed an interest in law, spending his days in the senator’s library studying. In 1850, he was admitted to the Georgia Bar. Soon after, the Civil War broke out in 1861 and Akerman joined the Confederate Army in 1863 to become a colonel, fighting in the Battle of Atlanta. The battle marked a significant victory for the Union. Once the war ended, Akerman joined the Republican party in 1865, becoming very outspoken about the civil rights of freedmen during Reconstruction.

From fighting for the Confederacy to defending Reconstructionist efforts, Akerman’s change may appear extreme, but it was actually bound to happen. When asked about his allegiance to the Confederacy Akerman said, “I gave it [the Confederacy] my allegiance though with great distrust of its peculiar principles.”

After the war ended, Akerman ensured that his vision for the proper principles of the South was reflected in his contributions to the 1897 Georgia Constitutional Convention. Akerman joined 139 other delegates to ratify the 14th Amendment, granting citizenship to the formerly enslaved, and creating Georgia’s new constitution. During Reconstruction, all of the former Confederate states had to create new constitutions that reflected their commitment to the United States’ post-Civil War and post-slavery vision.

Following his success at the constitutional convention, Akerman’s political career continued to grow when President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him as the Federal District Attorney for Georgia in 1869. A year later, Grant appointed him to be U.S. Attorney General at the Department of Justice. Akerman also began the investigative unit that is considered the precursor to the FBI. Today, the FBI is the investigative arm of the Department of Justice. The initial investigations were prompted by the violence perpetrated by the KKK in South Carolina. Akerman personally traveled to the state and uncovered “11 murders and more than 600 whippings and other assaults.”

Created in 1870, the Department of Justice was established by Congress to defeat groups in the South who were undermining the power of the Reconstruction Amendments through violence and intimidation. This made Akerman the first attorney general capable of utilizing the resources of the Department of Justice. Akerman’s prosecutions and investigations mark an important start for the DOJ, as they demonstrate the first interpretation of justice and the fundamental principle of protecting constitutional rights through the legal system. As Attorney General, Akerman took decisive action to ensure that the victims of the KKK received justice.

In a letter from 1871 to William M. Thomas, an African-American Republican politician from South Carolina who was part of that state’s constitutional convention, Akerman wrote:

“...within the past fifteen months a horrible amount of crime has been committed—that the State law has punished but a very little of it—and that of the greater of the crimes popularly known as Ku Klux crimes…

…These crimes were perpetrated under such circumstances as would have made detection and punishment easy, if the officers, jurors, and influential citizens had in good faith sought to detect and punish them… the necessity of the interposition of the Government of the United States in behalf of the oppressed citizens, is made clearly manifest.”

Prosecuting the KKK: U.S. v. Elijah Ross Sapaugh

This trial depicts both the cruelty of the KKK and the constraints on Akerman’s prosecution efforts, stemming from the debate regarding whether Akerman and the DOJ were operating within or exceeding their constitutional powers. David Corbin, a U.S. attorney in South Carolina, also led the prosecutions of the Klansmen and was a part of the trials.

Another relevant note is that information regarding the 1871-1872 Klan trials, which this case is a part of, is mostly presented in a general manner without specific outlines of the cases. There are few sources that detail the specifics of these cases. One of the only in-depth and thorough representations of the trials is in the research paper “The Great South Carolina Ku Klux Klan Trials” by Lou Falkner Williams.

From the reporting of this paper, we now know that the case of the U.S. v. Elijah Ross Sapaugh occurred because 80 members of the KKK broke into Thomas Roundtree's home to find guns that were allegedly on the property. Rountree, who was Black, shot into the crowd in an attempt to defend himself when the Klan broke into his home. His escape failed and his shot injured Klansmen Elijah Sapaigh, leading to the Klan’s full-force attack. Roundtree allegedly had 35 bullet holes in him and Henry Sapaugh, Elijah’s brother, slit Roundtree's throat as well.

Due to these extremely violent acts, Sapaugh faced six charges, which were meant to stretch the federal power to prosecute the Klan Member to the fullest extent. These charges included two counts of murder while denying Rountree his rights, one by shooting, and another by slitting Roundtree's throat. This was followed by conspiracy against Roundtree's Second Amendment right to bear arms and conspiracy against Rountree for voting. Overall, Sapaugh’s case was a trial for conspiracy to deny Black Americans their right to vote, as Thomas Roundtree was targeted and murdered not solely because the KKK believed that he owned guns, but also for voting a Republican ballot.

Voting a Republican Ballot in the South meant making Reconstruction efforts a reality by providing political power to the party that strived to generate equality for Black Americans. Sapaugh and the Klan were trying to destroy these efforts in this act of mass violence, which would ultimately scare off others from voting. Thus, a conspiracy charge was established as the Klan conspired to undermine Roundtree’s constitutional right to vote and their intimidation would further hinder the voting efforts of others due to fear of violent repercussions.

The expansion in federal power is seen in Corbin’s inclusion of the conspiracy charge that explained the Klan’s attempt to violate Roundtree’s Second Amendment right to bear arms, given the attack was also initiated to find Roundtree’s guns. Roundtree legally had a right to his guns as an American citizen.

Based on the following charges, Sapaugh was found guilty. Yet, the case did not end there. As mentioned above, a large segment of the trials included debates about whether Akerman and Corbin had the federal authority to prosecute the various charges. This created a new ending for Sapanaugh, one where he was charged only for the lesser charge of conspiracy to violate Roundtree’s right to vote and not the two murder charges. Sapanaugh was charged $100 with a sentence of one year in prison. Nowhere is there a punishment for murder or violations of other rights.

With this baseline understanding of the impact of the limited authority Akerman and Corbin had during the prosecutions, it is important to understand how exactly this limit to their power occurred. It all revolved around the constitutionality of the Enforcement Acts. The Ku Klux Klan Act was also known as the Enforcement Act of 1871 and it allowed Akerman to arrest and prosecute Klan members. The purpose of the act was to allow the federal government to overthrow the Klan. This act was one of three Enforcement Acts designed to protect the rights of freedmen and guarantee that the newly established constitutional rights outlined in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were being actively upheld. Merely stating these rights in words wouldn't be enough to counter the racist endeavors of the Klan, so active efforts were necessary to enforce them.

Following the murder of Roundtree and the subsequent arrests of Klansmen, Akerman and Corbin engaged in a legal strategy that was unprecedented in American history, they worked to make the conspiracy to deny the civil right to vote a crime that can be prosecuted federally (based on the Enforcement Acts) alongside punishments for state crimes like murder, assault, and robbery. Corbin also attempted to attach further violations of 14th Amendment rights within the charges against the Klansmen because since Black Americans had become citizens they now had the right to equal protection under the law.This protection was thoroughly violated by the violence and terror inflicted upon Black Americans to deny them their newly won voting rights.

Unsurprisingly, the Klansman's defense counsel argued that equal protection laws do not constitute new federal crimes. They argued that equal protection and prosecutions are limited to state, and not federal, authority and that states must take it upon themselves to take action. The success of this argument meant that Akerman and Corbin could not attach state-level crimes to federal conspiracy crimes. This conclusion was reached by Judges Hugh Lennox Bond and George S. Bryan, who sided with the Klan’s defense attorneys. They agreed that the Justice Department was overreaching their constitutional authority through a broad interpretation of the amendments. However, the power to protect voters in federal elections was extremely important to the federal government, so Corbin and Akerman now focused their strategy on the conspiracy indictments.

The language of the court essentially stated that the equal protection amendment would only be allowed to be enforced by states of the former Confederacy, who were simultaneously allowing the KKK to terrorize the Black and Republican residents of their states. The decision in this case meant that the federal government essentially could not prosecute domestic white terrorists for the crime of murdering a Black person, and instead could only prosecute these terrorists for the far lesser charge of conspiracy, or the act of conspiring to commit a crime. Yet despite this significant setback, Akerman and Corbin still won 140 convictions on conspiracy charges against the Ku Klux Klan.

Due to these efforts, the presence of the Klan significantly diminished during Reconstruction, and the Klan would not return until their second founding in 1915 at Stone Mountain, Georgia. American historian William McFeely had this to say about Akerman, “Perhaps no attorney general since his tenure … has been more vigorous in the prosecution of cases designed to protect the lives and rights of Black Americans.”

Thank you so much for this very informative piece.