On August 4, 2022, Albert Woodfox passed away at the age of 75 from complications related to COVID-19. His is a name that few Americans know, but his life story articulates the complexity and gargantuan struggle America faces to liberate itself from ethnocidal oppression.

Woodfox, who is African American, belonged to the so-called “Angola Three” who were wrongfully convicted of killing prison guard Brent Miller in 1972, and spent more than four decades living in solitary confinement. Woodfox’s confinement is thought to be the longest stay in solitary confinement in American history.

In 1965, Woodfox, who was only 18 years old at the time, was convicted of armed robbery and sent to the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Woodfox has always professed his innocence to the charge of killing Miller and he believes that he was wrongfully convicted because he helped establish a chapter of the Black Panther Party while in prison and organized protests against the dystopian, Jim Crow era treatment being inflicted upon the majority Black prison population.

SCL The Word is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

The Louisiana State Penitentiary is located on what used to be an antebellum plantation, and it is commonly referred to as “Angola” prison because of the large population of Black Americans who have lived and were formerly enslaved in this area. It is believed these Black Americans were taken from Angola, and now the name of their former African home has become the name of their American prison.

As an inmate, Woodfox organized protests against segregation in the prison and the unpaid cotton picking Black inmates were subjected to in chain gangs across the outlying fields of the former plantation. As the civil rights movement spread across the country, Woodfox launched an extension of the movement within one of America’s most notorious prisons. As Woodfox fought for freedom and justice, American law enforcement responded by depriving him of even more freedom and forcing him to live in a 6ft x 9ft prison cell, devoid of human physical interaction for the next four decades.

Following his conviction, Woodfox, along with Robert Hillary King and Herman Wallace, were sentenced to solitary confinement. Woodfox stayed in solitary confinement for the next 43 years and ten months until he was exonerated in 2016. Woodfox was released from Angola prison on February 19, 2016 on his 69th birthday. The expectation was that solitary would psychologically break Woodfox, but he remained unbroken.

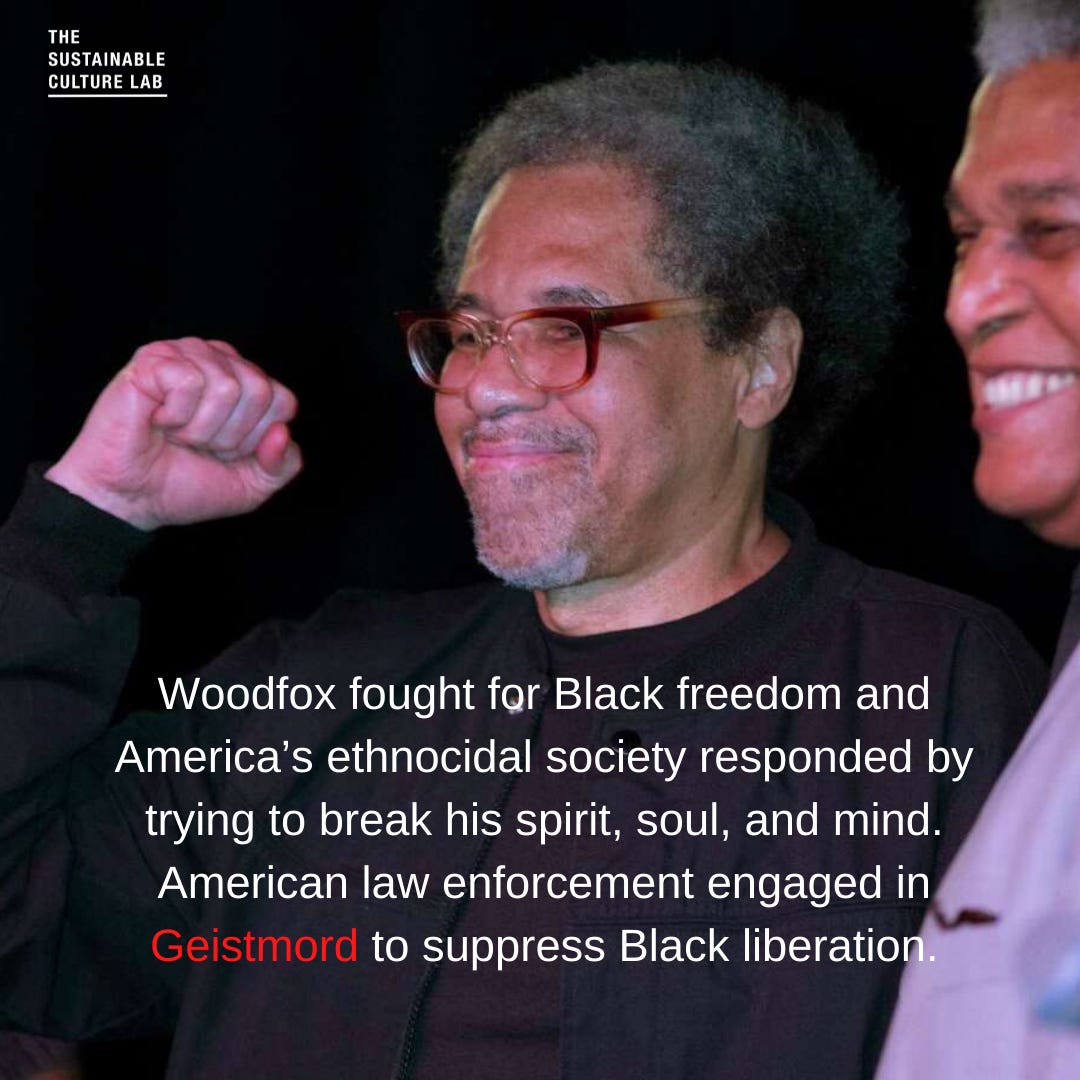

Woodfox fought for Black freedom and America’s ethnocidal society responded by trying to break his spirit, soul, and mind. American law enforcement engaged in Geistmord to suppress Black liberation.

Woodfox’s life shows the depths and horrors of American ethnocide in a modern context because he was first imprisoned as the Civil Rights act of 1964 and Voting Rights act of 1965 were going into effect, yet his incarceration had no desire to rehabilitate him, but instead wanted to turn him into a de facto slave from the 1800s via the practice of forced prison labor. The American government responded to Woodfox’s protests against his de facto enslavement by making a mockery of American laws through his wrongful conviction and increasing the cruelty of his imprisonment to an unprecedented degree.

Woodfox’s life story must remind all Americans that as progress is being made, American ethnocide is still capable of spreading regression.

To help sustain and grow The Word with Barrett Holmes Pitner we have introduced a subscription option to the newsletter. Subscribers will allow us to continue producing The Word, and create exciting new content including podcasts and new newsletters.

Subscriptions start at $5 a month, and if you would like to give more you can sign up as a Founding Member and name your price.We really enjoy bringing you The Word each week and we thank you for supporting our work.

The Need for Liberating Language

Woodfox’s life story is in many ways a Black American story, but most Black Americans will not have a life that mirrors his. His story is both familiar and foreign for Black Americans, and this seemingly contradictory dynamic poses a subtle linguistic problem.

His story is about the struggle for Black freedom in America, and the severity of the oppression from white America makes his story stand apart from the rest. His inhumane treatment makes his story unique, but the ethnocidal philosophy that condoned his oppression and the desire for liberation is present and felt across America’s Black community today. We are talking about a collective cultural desire to free our people from ethnocidal oppression, and this liberating journey unearths two profounding linguistic impediments that undermine Black progress and equality in America.

Firstly, the word “ethnocide” is not commonly known, and because of this many Americans remain unaware of what they are working to liberate themselves from. Black Americans may subconsciously or consciously know that they want to liberate themselves from America’s desire to destroy our culture while preserving our bodies, but it is much harder to advocate for change if the crime has never been named. Instead we may fight against racism or cultural appropriation without recognizing that they derive from ethnocidal roots.

Secondly, by acknowledging the full extent of American ethnocide upon the Black community, it becomes clear that preventing Black Americans from self-identifying has always been a part of American ethnocide. After European colonizers intentionally and forcefully worked to destroy African culture but keep African bodies, they set about renaming African people.

Our names were no longer associated with our African cultures, but instead reflected how European colonizers saw the people they decided to oppress. African people were called nigger, coon, negro, and colored. These words had nothing to do with the existence of Black people, and everything to do with the subhuman essence that white Americans chose to inflict upon us.

The capacity of America’s Black people to name one’s community and champion its existence poses an essentialist threat to American ethnocide that has long prioritized white American essence or identity ahead of non-white existence.

Woodfox embraced Black power, pride, and existence through the Black Panther party. He pushed back against American ethnocide so that he could exist as a human being and not as a de facto slave in a prison built upon a former antebellum plantation. By fighting for freedom and equality, America tried to kill his spirit.

Freecano: A Liberating Name

Since the 1960s, America’s Black community has embarked on a linguistic journey to self-identify with the embrace of Black power and pride being one of the pivotal steps along this journey.

Black usurped “colored” or “negro,” but black was an identity built upon a color and not a culture. In the 1980s, “African-American” emerged as a new term that allowed Black Americans to also embrace their pre-diaspora African culture. Yet African-American sounds more like the identity of an immigrant community and not the descendants of a multi-century atrocity whose ethnocidal philosophy still undermines our freedoms today.

Over the last three decades, “black,” with a lowercase “b”, and “African-American” have been essentially interchangeable, but recently there has been a call to capitalize Black because Black Americans are a culture of people and not merely a color.

I have been a long time advocate of this change, but I do not believe that Black should be the last step in Black America’s linguistic journey for freedom and self-identity.

In my book The Crime Without a Name: Ethnocide and the Erasure of Culture in America, I introduce the neologism “Freecano” as a potential next step in this linguistic journey. In my book, I discuss Freecano in more detail, so here is the abridged story of Freecano.

Freecano’s root word is “African” because at one point Black Americans were African people whose lives had not been tragically reshaped by ethnocide. However, our forced removal from Africa meant that we became African people forced to live outside of our home, so to symbolize this transition I removed the “A” from “African” to create “Frican.” (America’s Chicano community in southern California created the word “Chicano” by removing the “Me” from “Mexicano” and then changing the “X” to a “Ch” to symbolize a Mexican community that existed outside of Mexico.)

After being forcefully removed from Africa, Frican people we subjected to ethnocidal oppression and terror, and their communal bonds were systematically destroyed by European colonizers. Frican people united around their shared cultures, but most significantly they united around their shared desire to free themselves from ethnocidal oppression. To symbolize a culture forged by a desire to be collectively free, I changed the “Fri” to “Free” to create “Freecan.”

Lastly, to be more linguistically and culturally inclusive I added an “o,” which can also be an “a,” “e,” or “x,” to the end of “Freecan” to include the large Spanish or Portuguese speaking African diaspora communities in the Americas.

America’s Black, or Freecano, community is forged from the struggle to liberate our community from ethnocidal oppression, so our cultural name should reflect our shared culture forged by a desire to be free.

The physical, linguistic, and philosophical work to cultivate freedom has always defined our culture.

Woodfox’s life is a timely reminder of the need to continue this fight and strengthen our Geist. This Black August, please take the time to remember the Black American heroes who have championed Black freedom, and impacted our society for the better.