Part 1: Finding My History and Understanding the Present

Altaring America: How a Celebration of Ancestor Remembrance Can Alter America

This is post is part of series that will explain my journey to create and my vision for the Altar America Project, which centers cross-cultural ancestor remembrance practices as a vehicle for both preserving and creating culture in America, and as a means for transforming this nation into a more just, free, and equitable society.

This weekend, the Sixth Annual Altars Festival is being held in Richmond, Virginia from November 1 to November 8. To learn more, please visit the website.

I did not grow up with a cultural practice of ancestor remembrance, but I wish I had.

For the last ten years, I’ve been cultivating a cross-cultural ancestor remembrance practice that can be inclusive to my multi-cultural and racially diverse community of friends and family. The hope of this work has always been to help Americans—especially Americans of color—collectively cope with the trauma of loss and cultural erasure, and to also forge a sustainable and nurturing culture in America. For a decade, I have been experimenting with this idea and learning from other people. This journey has changed me for the better and I know that it can benefit millions of Americans too. This the Altar America Project and this is my journey.

I grew up in the suburbs of Atlanta, Georgia in the 1990s. My mother is from Charleston, South Carolina, and my father is from Prattville, Alabama. As Black Americans we always knew our history and we were proud to be Black, but we never had an annual practice, tradition, or ritual for ensuring that we kept our history and culture alive. As a child and young adult, I had no idea what I was missing, but now I do. This is why I want to altar America.

As Black Americans, our relationship with the past and our means for keeping it alive in the present have always been complicated and tense. More often than not remembering the past means unearthing past traumas and reliving stories that people may wish had remained buried. My parents grew up during the Civil Rights Movement and lived through desegregation. They met in Alabama in the 1970s and they moved to the suburbs of Atlanta in the 1980s. When I attended school, I was one of the few Black kids in my class, so I understand why they did not tell me stories about the violence white children inflicted upon them when they attended school. My parents did not want me to hate my neighbors and my classmates, so they refrained from telling me about the hatred inflicted upon them.

This decision is understandable and the intentions are noble, but it still amounts to an erasure of the past and an erasure of our culture. This is a situation where a good decision may not have even existed at the time, and the primary goal consisted of merely trying to survive while raising Black children who do not feel the pain of the previous generation’s trauma. I did not grow up consciously feeling the pain of past traumas, but I did have a quiet yearning to learn more about my family’s past. I knew that a piece of me was missing, and I knew that American society writ large would not help me fill this void. This was a quieter and more subtle trauma, but still a trauma.

When I reached my 20s and started approaching my 30s, I knew that I needed to learn more about my past so that I could chart my future. I needed to know more about where my people were from, so that I could know where I could go.

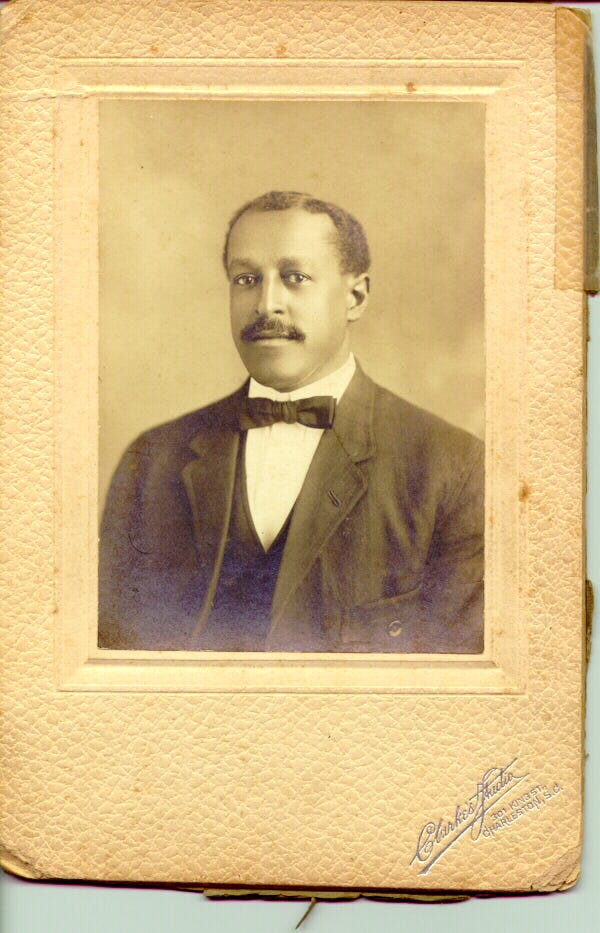

Fortunately for me, my Uncle Arthur had a similar yearning and unbeknownst to me had already started documenting and researching our family history on my mother’s side. Arthur had become the family archivist and through his work, I learned that one branch of my maternal lineage were free persons of color (FPCs) in Charleston since the 1790s and that the patriarch of another branch was the illegitimate son of a white plantation owner who died in the Civil War fighting for the Confederacy. Not only was my ancestor the illegitimate son of a Confederate soldier, but he was only one-eighth Black and was so light that he could pass as white. In fact, the Confederate soldier’s widow, even decided to raise my ancestor as her own son and he believed he was white until he was about 18 years old.

As a child I knew that some of my ancestors in Charleston were never enslaved, but I did not know the term “free persons of color,” and I had no idea that one of my Black ancestors grew up believing that they were white. In a moment, my culture, history, and family became more vivid. I could see the past more clearly, and as a result, could better understand my place in the present. From this moment forward, I stopped thinking about my life through my own lived experiences, or even those of my parents and grandparents; and instead starting to think about my life through the multiple generations that preceded me.

Doc Mack, my ancestor who believed he was white, was my great-great grandfather and was born in 1860. That’s only four generations of history.

John Hill II was born in 1790 and he was the first FPC in my family. That was only seven generations ago.

My history had been returned to me and this revelation radically altered how I saw the world. I thought about time in bigger chunks and I started thinking about America in centuries instead of in decades. Instead of thinking about the 1960s and the experiences of my parents, I started to also think about the 1860s and the life of Doc Mack, and the lives of my FPC ancestors who fled Charleston during the Civil War.

When Donald Trump first ran for president in 2015, and started calling Mexicans “rapists,” proclaimed that he wanted to build a wall along the southern border, and stated his desire to forcefully round up all undocumented immigrants and deport them; I did not think that these were the crazy ramblings of a rogue presidential candidate who would eventually fail and never become the president. When I heard his words, I thought about my FPC ancestors during the Civil War who, despite being free, now faced the threat of having their documents destroyed, so that Southern Confederates could justify their enslavement. To escape possible enslavement, many of my ancestors fled the country.

I wrote about this in my column for The Daily Beast titled “Ok, This Trump Thing Isn’t Funny Anymore.” This piece was the first mainstream article that compared Trump to fascism.

Trump’s threats to Latinos reminded me of the dangers my ancestors faced more than a century ago, and as Trump’s campaign continued his rhetoric increasingly resembled that of the Southern voices who opposed Reconstruction. Back then they called themselves “redeemers” because they wanted to “redeem” the South and return it to how it was before Reconstruction. Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement is the same idea but expressed at a national instead of a regional level.

To better understand 2015, I thought about 1860s. And to better understand the present, I still think about the 1860s and 1870s. My interest in Reconstruction grew because my history had returned. The Reconstructionist could not exist without this history.

My history had returned and it had become abundantly clear how this knowledge improved my life at a personal level, but also helped me better understand the changes that were starting to radically deform and regress this nation.

I knew the importance of finding and returning this history, but now I had to create a means for preserving it for generations. And I had to do this not just for myself, but for countless other people too.

This is when I started to learn about ancestor remembrance practices and began thinking about how I could altar America.

In Part 2, I will talk about how the Black Lives Matter Movement and Día de los Muertos transformed my relationship with my history, helped me deal with the trauma of loss, and allowed me to strengthen my friendships and cultivate new relationships.