Albion W. Tourgée: Forgotten Ally of Reconstruction

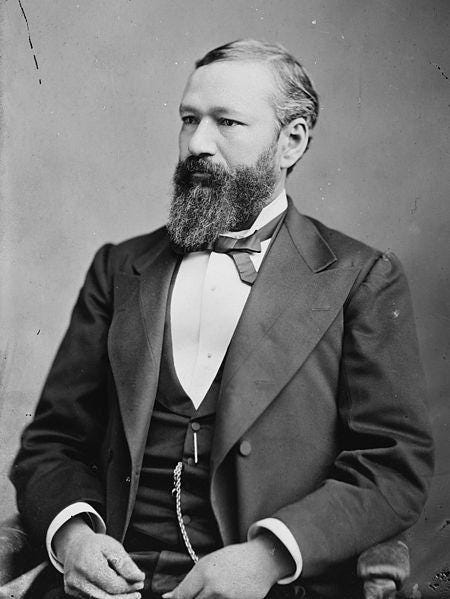

Most people have never heard of Albion Winegar Tourgée, yet his legal scholarship and committed advocacy of Reconstruction still influence us today. Tourgée is one of the many heroes of Reconstruction whose stories have been forgotten.

Tourgée was born in Williamsfield, Ohio, in 1838, and in 1861, he enlisted in the Union Army following the outbreak of the Civil War. During the First Battle of Bull Run on July 27, 1861, Tourgée was injured when a Union gun carriage struck him in the back, severely injuring his spine. Tourgée suffered temporary paralysis as a result of the accident, and he would suffer from chronic back problems for the rest of his life. Despite the severity of his injury, Tourgée made a sufficient recovery and continued to fight in the Union Army for two more years. However, due to his back and additional injuries, like being wounded in the Battle of Perryville in 1862, he was eventually forced to resign from the Union Army in 1863.

After leaving the army, he returned to Ohio and began to study law. Following the Union’s victory in the Civil War, the Republican Party encouraged northerners to relocate to the South, enabling them to assist in the region's reconstruction. In 1866, Tourgée and his family moved to Greensboro, North Carolina. Upon arriving in North Carolina, Tourgée established himself as a prominent journalist, lawyer, and member of the Republican Party.

His vocal advocacy for Black suffrage helped distinguish him from many of the white moderates within his party. In 1866, Tourgée attended the National Union Convention to help gather support for Andrew Johnson’s presidential campaign. At the convention, he attempted to push through a resolution in favor of Black suffrage. Unsurprisingly, Johnson--who, despite being Abraham Lincoln’s successor, was staunchly against Black suffrage–helped defeat Tourgée’s resolution. Black men would not obtain the right to vote until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

In 1868, Tourgée represented Guilford County in North Carolina’s constitutional convention. During the Civil War, the Southern states created new constitutions that pledged allegiance to the Confederacy. Following the South’s defeat in the Civil War, these states had to create new constitutions that pledged their loyalty to the United States. As part of Reconstruction, these new constitutions were required to support the Fourteenth Amendment. Tourgée helped draft North Carolina’s Reconstruction constitution, and his legal brilliance continues to benefit North Carolinians today.

In 2022, Daryl Atkinson, the co-founder and co-director of Forward Justice, a nonpartisan law, policy, and strategy center dedicated to advancing racial, social, and economic justice in the South, successfully used parts of North Carolina’s Reconstruction constitution to re-enfranchise formerly incarcerated North Carolinians. This was the largest expansion of voting rights in North Carolina since 1965.

Before Reconstruction, North Carolina’s constitution stipulated that North Carolinians needed to own five acres of land to be eligible to vote. At the time, this law was intended to disenfranchise poor whites in the state, but this standard took on a whole new meaning during Reconstruction. The Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 abolished slavery, and the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 granted citizenship to the formerly enslaved, but Black men did not obtain the right to vote until the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.

However, Tourgée had been championing Black suffrage since 1866 and understood how a similar provision in North Carolina’s new constitution would eventually disenfranchise Black voters. Due to this, Tourgée ensured that it would be unconstitutional to attach a property requirement to voting eligibility in the state. During Reconstruction, Tourgée’s work empowered Black Americans and poor white Americans, and more than a century later, it would empower the formerly incarcerated.

At the time of Atkinson’s lawsuit, North Carolina required that the formerly-incarcerated pay off various fines and dues, so that they could reclaim their voting rights, and Atkinson and his team successfully argued that these impediments were a modern-day property requirement. Tourgée’s work in 1868 helped enfranchise formerly incarcerated North Carolinians in 2022.

“White people have always had a role in fighting for justice. We just have to tap into the historical legacy-the Albion Tourgées,” said Atkinson, during a panel discussion hosted by the American Bar Association, titled “By Understanding Reconstruction, You Understand the United States.”

Despite Reconstruction’s collapse in 1877, Tourgée remained a vocal advocate for civil rights and racial equality. In 1890, Tourgée was contacted by a group of Black and creole Louisianians called the Comité des Citoyens (Committee of Citizens) to create an act of civil disobedience and a legal strategy to challenge the constitutionality of Louisiana’s Separate Car Act, which stipulated the Black and white customers must have separate train car accommodations. This case would become Plessy v. Ferguson, and Tourgée would be the lead counsel on the case.

However, if Tourgée had his way, Homer Plessy would have never been a part of this seminal case.

The plan constructed by Tourgée and the Comité des Citoyens required that a Black American intentionally sit in a “Whites Only” car, so that they could get thrown off the train car and then challenge the constitutionality of the law. Their strategy needed to challenge the integrity of the law, but also the absurdity of America’s racial divisions and the immorality of racial division and the violence that comes with it. To this end, Tourgée recommended that they enlist a Black American who could pass for white, and most significantly, he recommended that this person be a Black woman. Tourgée believed that the court might be more sympathetic to the image of an abused woman, and less inclined to legitimize a legal theory that condones the beating of women. And Tourgée had legal history on his side.

In 1868, a Black woman named Katherine Brown was beaten and thrown off a train because she sat in a “Whites Only” car. Brown’s injuries were so severe that she was spitting up blood and bedridden for several weeks. Since Brown worked at the U.S. Capitol, her prolonged absence was noticed by prominent politicians, including Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts and Justin Morrill from Vermont. As a result, the Senate launched a formal investigation into the railroad company, and Brown was awarded $1,500 in damages.

However, the railroad company challenged the decision, and the case ultimately made its way to the Supreme Court. To defend their act of terrorism against Brown, the railroad company argued that they provided equal, but separate accommodations for Black and white passengers, and therefore, did not violate their contract that stipulated that all passengers should receive equal treatment and service.

In 1873, in Railroad Company v. Brown, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Brown and ridiculed the railroad company’s argument of equal but separate accommodations according to race. In the Court’s decision, Judge David Davis wrote, “This is an ingenious attempt to evade compliance with the obvious meaning of the requirement. It is true the words, taken literally, might bear the interpretation put upon them by the plaintiff in error, but evidently Congress did not use them in any such limited sense.”

In 1868, a Black woman was the victim of segregationist violence, and the Supreme Court ruled that the segregationist theory of separate but equal was unconstitutional. Tourgée wanted to recreate this scenario from Reconstruction to continue the fight against segregation in the South. Who knows if Tourgée’s strategy would have changed the outcome of Plessy v. Ferguson and prevented the emergence of Jim Crow segregation, but it is worth thinking about. It would take another 60 years for the Civil Rights Movement to launch and for Rosa Parks to refuse to give up her seat on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

Despite Tourgée’s recommendation, the Comité des Citoyens in 1892 decided to enlist a mixed-race Black man named Homer Plessy to sit in the Whites Only train car, and as planned, this case made it all the way to the Supreme Court. During the trial, Tourgée employed an ingenious legal argument that he called “color blindness,” which he had first developed during Reconstruction, back when he was a Superior Court Judge in North Carolina. Tourgée argued that the law needed to be color blind to ensure that all Americans were treated equally, and that separate but equal was not colorblind. Tourgée is credited with introducing “color blind justice” to American law.

In 1896, the Supreme Court, in Plessy v. Ferguson, ruled against Plessy and dismissed Tourgée’s theory of color blind justice. Soon thereafter, Jim Crow segregation and American apartheid became the new status quo. The progress of Reconstruction was dismantled piece by piece, and Tourgée became a forgotten figure in American history.

After Plessy, in 1897, President William McKinley named Tourgée the American consul in Bordeaux, France. Throughout his lifetime, Tourgée remained active in the Republican Party and formed close friendships with presidents McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. They were among the American leaders with whom he kept up correspondence and writing, sharing his thoughts on racial relations and the difficulties of the post-Reconstruction period.

On May 21, 1905, Tourgée passed away in Bordeaux due to acute uremia, which may have been caused by an injury sustained during the Civil War. Tourgée was buried in Mayville, New York, and the inscription on his tombstone reads: I pray thee then Write me as one that loves his fellow-man.

In November 1905, the Niagara Movement, founded by W.E.B. Du Bois, and the precursor to the NAACP, organized a nationwide memorial to celebrate Tourgée’s life. The memorial celebration was called “The Friends of Freedom” and celebrated Tourgée alongside William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass.

Albion Tourgée should be a household name in the United States, but the demonization and erasure of Reconstruction from our collective memory means that heroes like Tourgée are also forgotten. If we are to Reconstruct this nation, we must learn about, remember, and celebrate our heroes, our “friends of freedom,” from Reconstruction.

The first issue of the New york trade journal newpaper The Journalist wrote a scathing article on him: https://www.loc.gov/resource/2023270549/1884-03-22/ed-1/?sp=1&st=pdf&r=-0.275%2C-0.055%2C1.549%2C1.549%2C0. Is the criticism here justified?