Everyday Eǔtopia • noun • (ev-ree-day ev-toh-pee-a)

Definition: the act of cultivating Eǔtopia on a daily basis

Origin: The Sustainable Culture Lab

To help sustain and grow The Word with Barrett Holmes Pitner we have introduced a subscription option to the newsletter. Subscribers will allow us to continue producing The Word, and create exciting new content including podcasts and new newsletters.

Subscriptions start at $5 a month, and if you would like to give more you can sign up as a Founding Member and name your price.

We really enjoy bringing you The Word each week and we thank you for supporting our work.

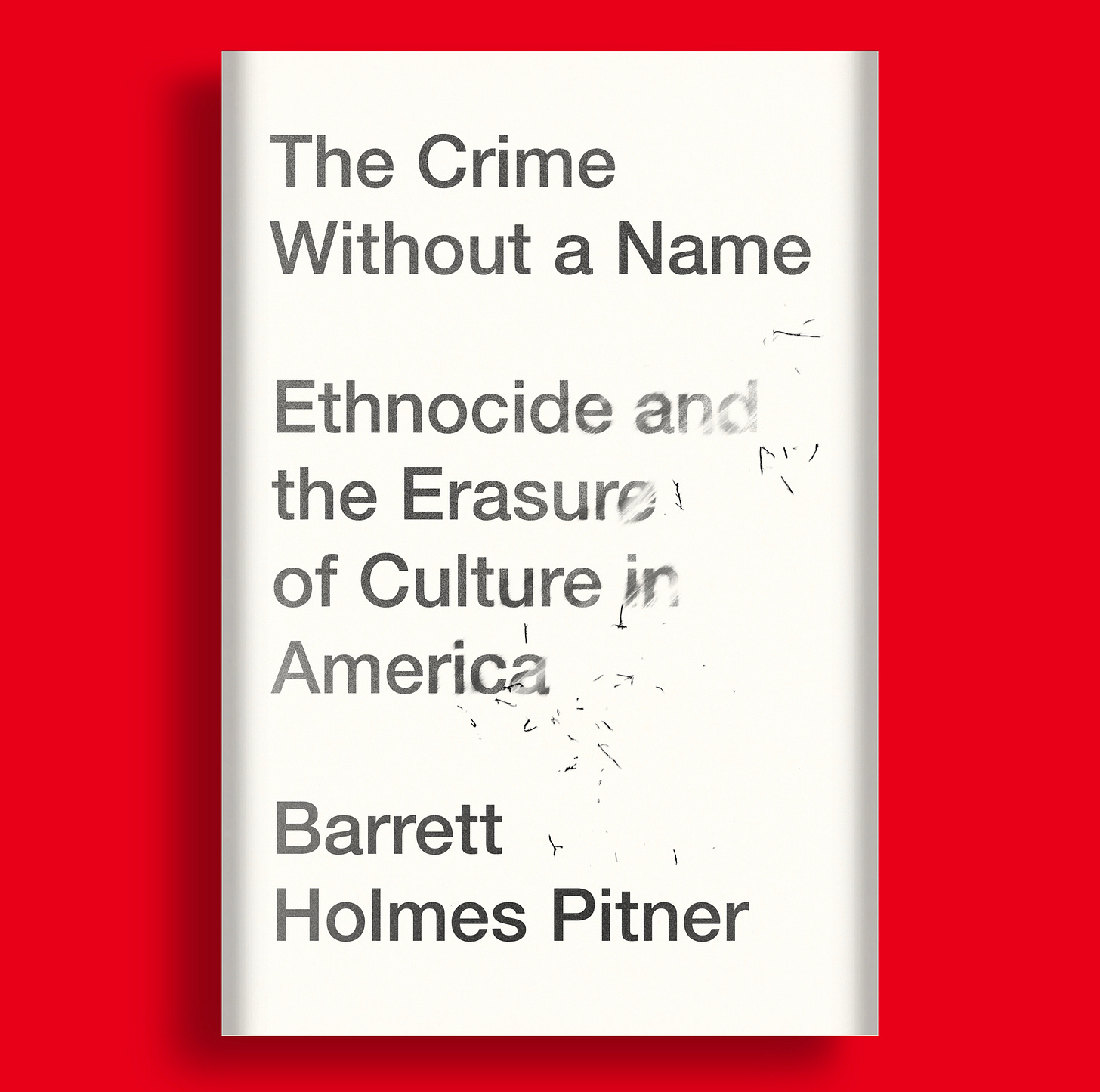

The cover art for my book has been released! You can see my book cover at the end of the newsletter.

Pre-orders for Barrett Holmes Pitner’s book THE CRIME WITHOUT A NAME are now available. You can place those orders through your local independent bookseller, or any of the following: Bookshop.org | Amazon.com | Barnes and Noble

When we launched this newsletter a little over a year ago, the first word we wrote about was Eǔtopia, which means a sustainable and nurturing good place. In that newsletter, we explained how and why “Eǔtopia” is different from “utopia,” which we strongly recommend reading if you haven’t already done so.

The reason we chose Eǔtopia as our first word was because we wanted readers to know that our work was more than merely highlighting and combatting ethnocide. We must be able to react to the bad things in our world, and we also must be able to proactively cultivate a good place. Our work has never been about merely abolishing the bad because once you succeed in this endeavor, you must also have the language, philosophy, and practices for cultivating the good.

Within an ethnocidal society, we can dedicate our lives to defeating the myriad of bad, unsustainable, and dystopian practices that define this environment. This seemingly unending battle can define our existence and result in us not dedicating enough time to how we define, articulate, cultivate, and sustain our new environment after abolition succeeds. Without a focus on a proactive good, we can easily find ourselves in an unending cycle of abolition with success far away on the horizon.

Eǔtopia is proactive and is not a reaction to ethnocide, and this proactivity is a key ingredient to dismantling ethnocide. If we exist to respond to ethnocidal oppression, then we allow for ethnocide to have the upper hand and it becomes much harder to defeat this oppressive norm if we allow it to take initiative.

For myself, cultivating Eǔtopia has been much harder than raising awareness of ethnocide. Employing a new language for articulating America’s systemic oppression is actually a process that America has engaged in numerous times. We all know there is a problem with our society, but the process of accurately naming this problem has long been our dilemma. At The Sustainable Culture Lab, we are part of this American linguistic journey, but our language also requires that we cultivate the essential tools for living in a post-ethnocidal society. This process has proved alarmingly difficult.

Everyday Eǔtopia

When we first started talking about Eǔtopia, people immediately wanted to know how we could get there. It’s easy to misinterpret Eǔtopia and perceive it to be a more palatable utopia because now the word finally means “good place,” but Eǔtopia is anything but a new word for the same idea.

At first, people saw it as a mythical place that existed on the other side of the ocean or a mountain range. It was a perfect place that already existed and was awaiting our arrival. It was a place we had no role in creating. People did not seem to want to create a good place, but instead find one that other people, real or mythical, had created and then start living there. The dream was not about cultivating good ourselves, but about invading somebody else’s good place.

This aspiration was anything but good and anything but Eǔtopian. It was passive, dystopian, and riddled with colonialistic undertones. Eǔtopia is a good place that we create, not one we discover. Now we have to begin the work of articulating how one can create Eǔtopia.

When you try to envision a “good place,” the inclination is to think about something big. People normally want to dedicate time focusing on the macro and an idea that will change the world. At SCL, we took a different approach and instead thought about what each of us can do to make ourselves into “good places” and then grow from there. This is where the concept of Everyday Eǔtopia came from.

To a certain extent, the idea for Everyday Eǔtopia came from my friend Max. Max has always been a person who values his hobbies and cultivating routines. His hobbies remain hobbies. He does not discuss his hobbies as if they are his profession or if they are superior to another person’s interests. His hobbies are simply things he is interested in, and he consistently dedicates time to pursue his hobbies. His hobbies are sustainable, nurturing activities that he makes sure that he regularly cultivates. For a long time, I have appreciated his hobbies but I did not have a word for them, and then it dawned on me that these are Eǔtopian practices.

During COVID-19, Max decided to pick up drawing and dedicated himself to completing a drawing every day--you can look at his drawings on his Instagram @sketchtothemaxx. It was great seeing him get better and better as he pursued what I considered a small Eǔtopian practice each day.

One’s Eǔtopian practices can be small actions that others might overlook, but if you infuse them with your geist, they can soon become founts of meaning, purpose, and goodness.

After thinking about Max’s drawings, I decided to ask the team at SCL to practice Everyday Eǔtopia. Each week we cultivate some action or routine and consciously understand it to be an expression of Eǔtopia. Some have decided to pick up painting or rekindle a neglected interest that they believed they had been too busy to pursue. Others used the language of Eǔtopia to inject greater meaning and intention into actions that started to seem meaningless. Gardening, spending time with friends and family, and even cleaning the house, now became small expressions of the sustainable, good place they aspired to cultivate.

Everywhere Eǔtopia

When you attune your thoughts to cultivating Eǔtopia, you soon realize that there are many practices from around the world to help inform us about how to lead good, sustainable, and nurturing lives. Here are a few words that we’ve covered throughout this newsletter that can help us create good places at the micro and macro levels: ubuntu, geist, nervenstärke, éist, reconstruction, Freecano, sama-sama, moai. The hope is that once we can see and say Eǔtopian philosophies and practices, we will be much better at implementing them.

Eǔtopia is not perfect and sometimes it is not even fun. As part of my new routine, I have started ending my showers with 30 seconds of a cold shower, and when I first started doing it, it definitely was not fun. I added this practice to my routine because cold water is supposed to strengthen your immune system and help your muscles recover from exercising.

The goal of Eǔtopia is not to have individuals or places that are perfect and never making mistakes, but instead have a good, sustainable, and nurturing philosophy so that these entities know how to recover and pick themselves up when they inevitably make mistakes. It is worth repeating that Eǔtopia cannot exist without effort. It is a place that will never exist unless we make it.

By understanding Eǔtopia, it becomes much easier to cultivate Eǔtopia everywhere.

This week, please start engaging in Everyday Eǔtopia by using the hashtag #EverydayEutopia and share with us the practices both big and small that you have decided to cultivate.

Here’s the book cover for The Crime Without a Name: Ethnocide and the Erasure of Culture in America. You can pre-order the book here.