Corruption • noun • (kurr-upp-shun)

Definition: misleading others or the public for private gain; a foundational principle of ethnocide

Origin: English

To help sustain and grow The Word with Barrett Holmes Pitner we have introduced a subscription option to the newsletter. Subscribers will allow us to continue producing The Word, and create exciting new content including podcasts and new newsletters.

Subscriptions start at $5 a month, and if you would like to give more you can sign up as a Founding Member and name your price.

We really enjoy bringing you The Word each week and we thank you for supporting our work.

My book THE CRIME WITHOUT A NAME was released on October 12, 2021 and NPR has picked it as one of the top books of the year!

You can order the book—including the audiobook—and watch recordings of my book tour discussions at Eaton and the New York Public Library at thecrimewithoutaname.com.

Corruption is a word that we all know, but do not actually know. We hear about corruption nearly every day, and especially when discussing politicians and government officials. American governmental systems including law enforcement are often described as corrupt.

Yet despite how often we use this word, our understanding of corruption tragically remains mostly a reactionary word for describing something that systemically goes wrong and the culprits rarely receive adequate punishments. For the most part, we remain unaware of the philosophy that cultivates corruption, and an ethnocidal society thrives off of the normalization of corruption.

Philosophically, corruption is a manifestation of living in bad faith, or mauvaise foi. Bad faith depends on deception and lies, and it aspires to coerce someone to do something they otherwise would have no intention of doing. An ethnocidal society depends on bad faith because no person would knowingly agree to allow another person or group of people to destroy their culture for the benefit of the other group and the detriment of themselves, yet this is what ethnocide requires. If one knew the intent of the ethnocider, they would never interact with them. Therefore, the ethnocider must deceive and act in bad faith to perpetuate their ethnocidal agenda.

By engaging in mauvaise foi, the ethnocider is willing to corrupt the meaning of everything they touch so long as it helps them destroy the culture and existence of other people. For example, an ethnocider will describe themselves as a good person and tell you what you want to hear, so that they can convince you that they have both character and intentions that they do not possess. An ethnocider not only lies to other people, but often lies to themselves to convince themselves that their lies are not bad.

The ethnocider is the precursor to the corrupt American politician who convinces the public that they have the public’s best interests at heart, yet only wants political power so that they can enrich themselves.

Former president Donald Trump is the epitome of a corrupt politician, but his corruption exceeds the political realm. He exists as a corrupt individual who will manipulate anyone and anything for his personal gain. He manipulates his tax returns so that he hardly has to pay any taxes. And up until the recent investigation by the attorney general of New York, Trump had even described his corrupt tax filings as proof of his intelligence.

American individualism proclaims that there is a collective benefit in all Americans prioritizing their self-interests ahead of the collective, it should be obvious how this belief encourages corruption. America’s cultivation of corrupt individuals as makes Americans not only tolerate, but embrace blatantly corrupt people like Trump and his family.

In America, the ethnocider considers corruption to be a foundational aspect of their life—they believe it is “natural” to mislead the public for personal gain, that everyone would do the same in their position—and the normalization of corruption is baked into America’s ethnocidal status quo.

The Corruption of Culture

Ironically, culture is also a word that Americans know, but do not actually know.

During the initial drafts of my book The Crime Without a Name: Ethnocide and the Erasure of Culture in America, my editors recommended that I explain the meaning of culture very early in the book because they wondered if my readers had a clear understanding of the meaning of culture. This is why the chapter on polderen is chapter 2 and not chapter 6 or 7 as I had originally intended.

For many of us, “culture” has remained an ambiguous term. We seem to recognize culture when we see it, and we acknowledge that various places have their own “cultures,” but we do not have a common philosophical understanding of culture.

America lacks this cultural clarity because ethnocide has corrupted culture.

As I define in my book, culture consists of a group of people coming together and figuring out what they need to create and sustain in order to survive in a particular place and time. The culture of a society in a warm climate will be vastly different than that of a society in a cold climate. Neither society is better than the other, but they are different because they need to cultivate different things in order to survive. Their food, clothes, houses, and language will be very different because they need to be different so that they can survive in each place in perpetuity.

The Dutch word polderen is a great example of the natural connection between culture and collective survival because the word describes the cultural togetherness of Dutch people as they have collectively worked for a millennium to prevent their land from being swallowed up by the North Sea. Without polderen, the Netherlands might be underwater and Dutch culture would have literally drowned.

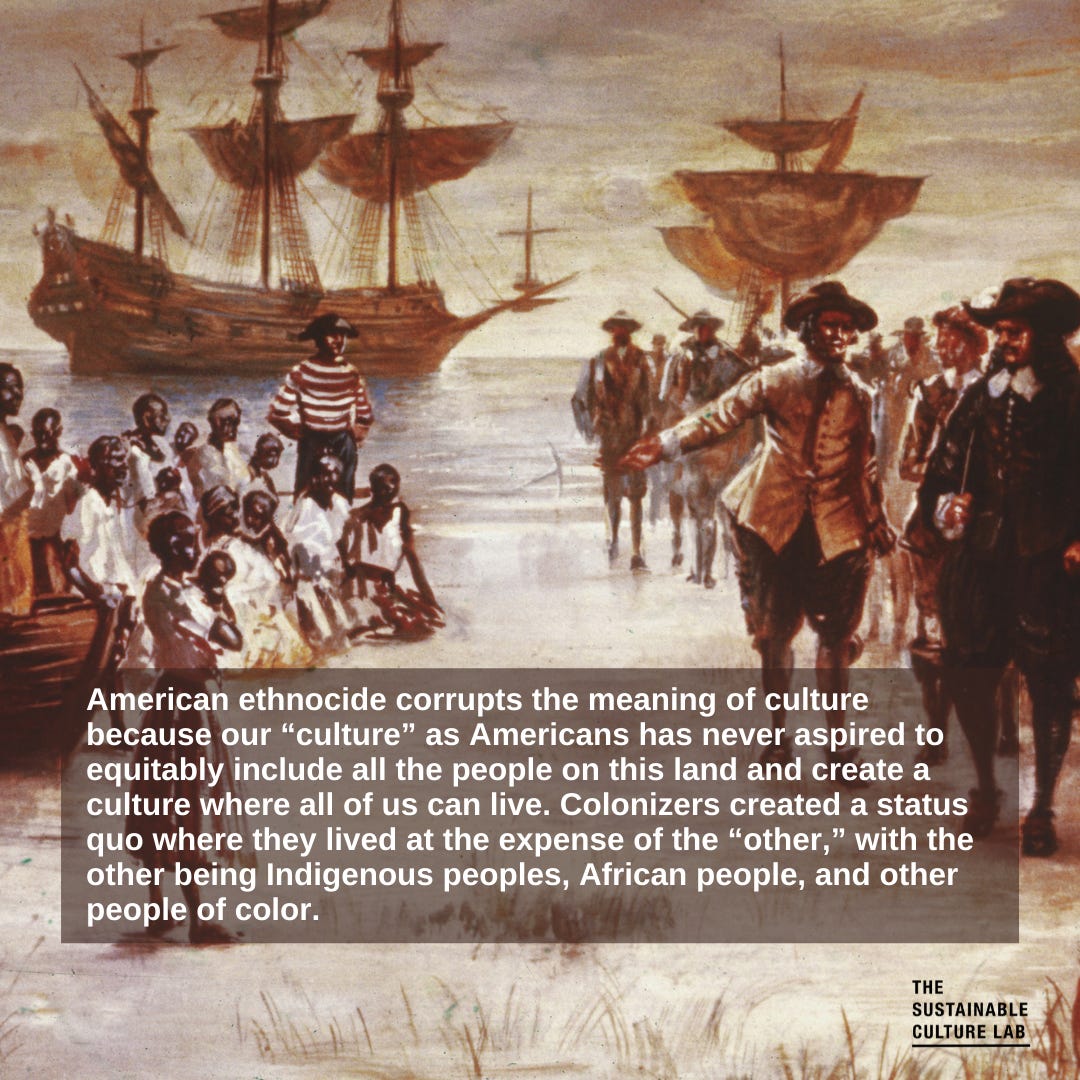

American ethnocide corrupts the meaning of culture because our “culture” as Americans has never aspired to equitably include all the people on this land and create a culture where all of us can live. Colonizers created a status quo where they lived at the expense of the “other,” with the other being Indigenous peoples, African people, and other people of color.

An ethnocidal “culture” is not actually a culture because it has no interest in collective survival, so it actually exists as the opposite of culture. However, an ethnocidal “culture” does have an interest in living in bad faith, and making people believe that it is something good when it is in fact something bad.

Ethnocide’s interest in the latter and disinterest in the former is both why America describes its absence of culture as “culture,” and why Americans have a vague understanding of culture. If Americans truly understood the meaning of culture, then they could easily see that America does not have one. By existing in good faith and recognizing the state of our cultural corruption, Americans could clearly see and understand the bad society that we live within.

Tragically, the difficulty of living your life in good faith within an ethnocidal “culture” encourages far too many Americans to embrace our cultural corruption and traumatize people of color, so that they can sustain our ethnocidal status quo and find happiness, wealth, and property at the expense of the other, the ethnocidee.

The Corruption of Language

In America, people often use the phrase “talk is cheap,” and these three words highlight the systemic corruption of American English, a topic we have discussed many times in this newsletter.

Americans believe that “talk is cheap” because we believe our words are empty and meaningless. We do not believe that people will follow through with the actions they say they will do, and linguistically we have this lack of faith in our language because we exist within a society governed by bad faith.

The ethnocider professes the benevolence of a culture of people who say one thing and do another. Those who implement ethnocide must lie to the people they intend to oppress so that they can coerce them into entering a relationship that they believe is based upon good faith, when bad faith is the sole agenda. Additionally, the ethnocider often must lie to themselves so that they can believe that their bad actions are actually good actions.

For example, in the Antebellum South, slaveowners had convinced themselves of the lie that enslaved people were so mentally inferior that they could not survive on their own as free people. Therefore, within this foundational lie the slaveowner had now become a “good” person because they “took care” of the people they had enslaved.

The lies, or mauvaise foi, that these ethnocidal Southerners had convinced themselves were true had created a language where benevolent words are being used to describe atrocities. Chattel slavery has been renamed as “taking care” of African people. This is a corruption of language akin to dystopian fiction, but this process of redeeming bad, corrupting people and calling them good has been America’s foundational status quo.

This corruption of American English means that people can say the same words while meaning the opposite of each other. If words do not have a consistent meaning, then talk will become cheap because language has been rendered essentially meaningless and we can never expect people to do what they mean because they do not mean anything.

In fact, within an ethnocidal society, the anticipated meaning of nearly any word is that it will be weaponized so that an ethnocider can attempt to profit at the expense of another person. The language exists within an perpetually corrupted state, and linguistic honesty exists as both something that people crave and know cannot survive within their ethnocidal culture.

At SCL we work to cultivate an uncorrupted language, and the recognition of American ethnocide is the first step to understanding and recognizing America’s pervasive culture and language of corruption.